Check out Part 1 here.

In practice, we use a combination of note names and intervals to navigate the fretboard. Note names are our GPS: they get us to the right place on the fretboard, then when we’re in the right place, we use intervals to get around.

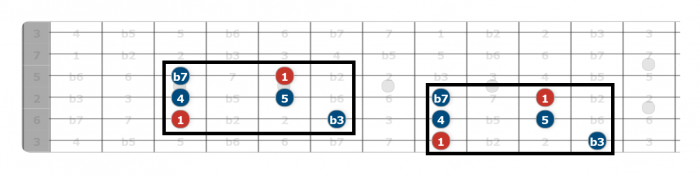

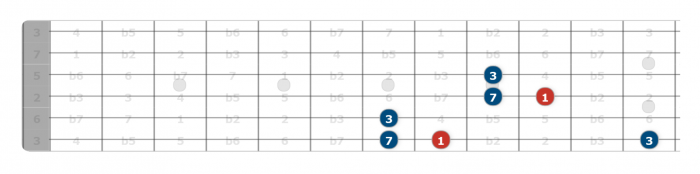

Let’s say we want to play the C Minor Pentatonic scale. Knowing the notes on the neck enables us to find all the C notes available to us, then when we know where those C notes are, we can move around using intervals.

We use intervals because (i) they tell us more information about the function of a note in a scale, chord or arpeggio, and (ii) it is far easier to then transpose this information to any other root.

Once we know where our C notes are, we can then use intervals to move around and get the sounds we want. In any scale, chord or arpeggio the 3rd and the 7th are going to be the defining intervals, so we need to know where these are. In our minor pentatonic scale, we have a b3 and a b7. We also have a 4, which is the weakest note in this scale and a 5, which is another strong tone. Just the note names themselves don’t really convey this information.

The diagram below shows more instances of C Minor Pentatonic to show you that we’re breaking away from conventional ‘box shapes’ to really choosing the notes/intervals we want to play. For example, you may want to use the C on the first fret of the B string, only there’s no immediate box pattern because you run out of fretboard, so you need to go up the neck to complete the scale—these are the kinds of things you won’t learn from scale patterns and boxes.

From the C on the eighth fret of the low E string we can play the b3 on the next string instead of the same string and move in a different way across the fretboard. These are the kinds of nuances we’ll be exploring in this series as we move from shapes and patterns to really knowing the fretboard.

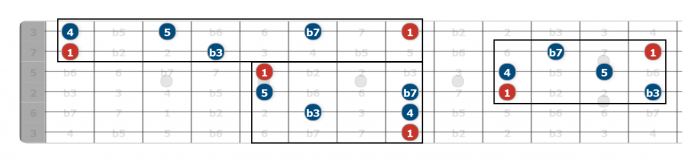

3 and 7 Combinations I

The first intervals to get to grips with are the 3 and 7 in all their combinations (don’t worry, there are only four) as within ANY scale, arpeggio or chord, the 3 and the 7 are the defining intervals.

The shift I want you to make here is from just diving into a scale or arpeggio and seeing what happens to looking at the fretboard and intentionally choosing which intervals to play.

Quick Myth Buster: Playing what’s in your head is NOT a literal concept or some holy grail to strive for due to two main factors; (i) you would need to be constantly composing while improvising to actually have something in your head all the time, which would also tire you mentally fairly quickly, and (ii) most of the time there’s nothing in your head because you’re reacting to what everyone else is playing, and (iii) it’s inevitable (and absolutely valid) to fall back on stock licks, runs and stuff you know WORKS.

Let’s stick with C as our example root and see how this works on the fretboard.

Major 3rd + Major 7th

As you can imagine the combination of a major 3rd and a major 7th will produce a major sound. You can find these intervals in:

-Major scale (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7)

-Lydian scale (1, 2, 3, ♯4, 5, 6, 7)

-Major 7 chord (1, 3, 5, 7)

-Major 7♯5 chord (1, 3, ♯5, 7)

-Major 9 chord (1, 3, 5, 7, 9)

What I want you to notice here are the options you have for hitting these intervals. This is not immediately obvious when you think in terms of scales as the intervals are defined by the scale pattern in linear fashion, meaning you probably wouldn’t think too much about whether you want to play the major 3rd on the same string, on an adjacent string, or on another string entirely.

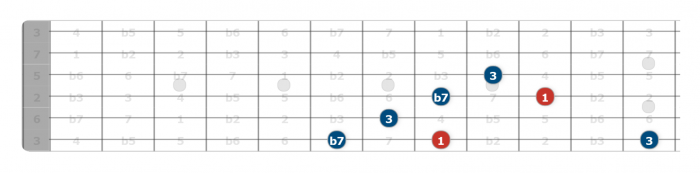

Major 3rd + Minor 7th

This is the key to the dominant sound you find in 7th, 9th 11th and 13th chords.

Again, notice where the b7s and major 3rds are in relation to the root. You will find this combination in dominant chords, arpeggios and scales such as the Mixolydian (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, b7) and various others.

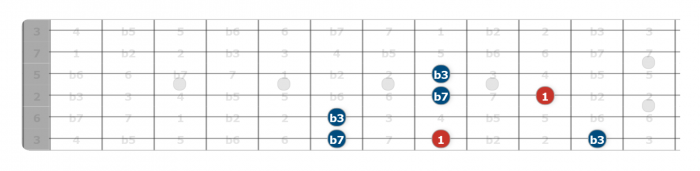

Minor 3rd + Minor 7th

This combination is prevalent in many minor scales such as the Natural Minor/Aeolian (1, 2, ♭3, 4, 5, ♭6, b7), Dorian (1, 2, ♭3, 4, 5, 6, b7), Phrygian (1, ♭2, ♭3, 4, 5, ♭6, ♭7), the Minor Pentatonic (1, ♭3, 4, 5, b7) etc.

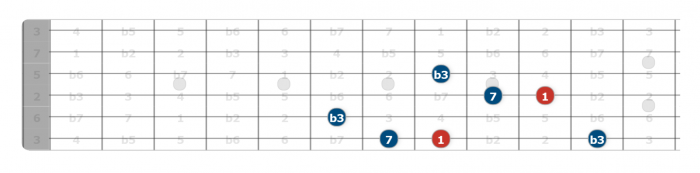

Minor 3rd + Major 7th

This combination is found in the more exotic-sounding scales, arpeggios and chords such as the Melodic Minor (1, 2, ♭3, 4, 5, 6, 7), the Harmonic Minor (1, 2, ♭3, 4, 5, ♭6, 7) and many others.

It makes sense that having an awareness of these four combinations and where to find them will give you access to the two defining intervals in any chord, arpeggio or scale in relation to the root.

In Part 3, we look at more of these combinations, as well as other intervals.