Following on the from the lesson on Parallel Thinking, I thought it would be useful to take a deeper look at the role of scale patterns in learning to improvise, and what I call Zonal Improvisation. According to various sources, patterns and boxes have been around since the early sixties, perhaps even before, and especially for jazz guitar as instructors felt that standard notation wasn’t able to convey the complexity of jazz guitar chords and scales as regards locating them on the fretboard. On the other hand, if you’ve ever studied classical guitar, you’ll know that it is mostly taught through standard notation with little reliance on scale patterns and chord boxes, so why isn’t this prevalent in almost every other style of guitar playing?

If you remember learning your first few cowboy chords on guitar, you most likely learned shapes first, and like me probably still think of the open D chord as a little triangle. It’s only years later that you realize it contains the notes D, F# and A, and the intervals 1, 3, and 5. A classical guitarist would know this almost from day one, and the pattern would be a by-product of learning through notation, much like the process we looked at in The Problem with Shapes and Patterns on Guitar. Most standard notation for guitar conveys how the piece is supposed to sound, as well as the rhythm and tempo at which to play it. What it doesn’t convey (in most cases) is exactly where to play it on the guitar; (un)luckily for us, any collection of notes can be played in different locations on the neck, and it’s very much up to the player to work out the best/right place to play it.

The Classical Approach

If you’ve ever checked out Al Di Meola’s book, ‘A Guide to Chords, Scales and Arpeggios’, you’ll know that the scales and arpeggio sections are written out in standard notation. I think this was the first (and only) book I had where scales and arpeggios were written out this way instead of box patterns or tab, and you’re encouraged to read the scales rather than working out the box patterns and becoming oblivious to the notes and intervals in the scale. Reading scales is something few guitarists probably do but once you try it, you realize what you’re missing out on.

The Other Problem with Patterns

If you run a scale pattern from the 3NPS or CAGED Systems after reading a scale from notation and finding the notes yourself, you’ll see that the ‘systems’ are in fact arbitrary sequences of notes that fit into a section of the fretboard and cover all the possible notes within reach for whatever scale you’re playing; in other words, this is their ‘default’ layout on the fretboard. If you think about it, learning scales via arbitrary boxes is pretty much exclusive to the guitar, and musically-speaking a rather odd way to learn scales. Patterns sacrifice the musical aspect of learning scales and turn it into a cold, mechanical exercise that leads to very scalar improvisation without much musical content. But doesn’t everyone learn scales this way? Pretty much, but that doesn’t mean it’s gospel.

The Pentatonic Box 1 Trap

But wait! I can rip out a sweet solo using box one of the minor pentatonic which I learned how to do by learning the scale pattern. Yes, but the thing about the minor pentatonic box 1 is that the notes fall so unbelievably nicely under your fingers that you’d have to make a humongous effort to play something that sounded bad in this position—in other words, you can’t go wrong with box 1.

Now, grab one of your 3NPS or CAGED patterns and do the same—for most players this is a little tricky because the notes don’t fall nicely under your fingers and in learning just the pattern, you sacrificed the musical content for an empty visual reference, which means that any attempts to be musical are somewhat of a shot in the dark because you don’t really know what you’re playing. I’ve often thought that this is why guitarists tend to overplay—it’s not that they’re into gratuitous soloing—they’re just trying to find some music within those generic patterns.

The Problem

My first guitar teacher once said to me, ‘Your average sax player can improvise 10 times better than your average guitarist, you know why?’

‘Why?’

‘They know the shit out of chords and scales.’

This is probably true for many other instruments where the player is not ‘shooting in the dark’ because they know which notes they’re playing and their function against the chord (intervals). Us guitarists, however, usually wait until we’ve hit a wall before we contemplate learning what are considered fundamental skills on any other instrument.

The Solution

To be honest, I discovered that most players aren’t fascinated by the idea of reading scales from notation, especially if they’ve already paid their dues in the woodshed and learned all their scale patterns. The problem was that their improvisations were technically very good but musically hit and miss which leads to the age-old question of, ‘how do I break out of scale patterns?’ Or, ‘how do I make music from scales?’

If you ‘break out of a scale pattern’, where do you go? To another scale pattern with the same notes? To the notes that aren’t in the scale? To some kind of elusive area of the fretboard where everything you play makes you sound like the ghost of Hendrix? What guitarists really mean by ‘breaking out of scale patterns’ is, ‘how can I be more melodic?’ Or, ‘how can I improve my phrasing?’ If you can’t be melodic or phrase well in one position, chances are you won’t be able to in another. This is where I came up with the solution, which is more of a compromise between ‘reading’ what you’re doing, and working with a more improvisation-friendly scale pattern in a reduced area of the fretboard, or what I call, Zonal Improvisation.

Here’s an example:

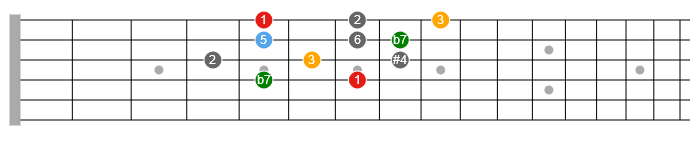

There are 5 interconnecting zones on the fretboard which lend themselves well to constructing scale patterns that are more comfortable to solo with than their CAGED or 3NPS counterparts. Here’s a Lydian b7 scale pattern in Zone 2:

Zone 2 is great because your hand is in the same position it would be for the minor pentatonic scale, and what you have is a one-octave scale shape containing all the notes of the scale and a few others that you would naturally move to when going to the adjacent zones or for helping with phrasing. This scale (here in A) works well over a dominant 7 chord so play one and run the scale, or loop one if you have a looper, or just use the low A string as a drone. The idea here is to use the pattern as a springboard to come up with your own phrases, lines and runs; not learn more patterns or patterns inside of patterns. Play as slowly as you need to be aware of which interval you’re going to next. If you play just the colored notes, you have the 7 arpeggio; try bringing in the other notes against the arpeggio sound, especially the #4, and you should be able to come up with some cool stuff, even if you’ve never used this scale before.

Compare what you just did to trying to be musical with the generic melodic minor/Lydian b7 scale pattern (Lydian b7 is the fourth mode of the melodic minor scale), and you’ll see a gaping difference in musicality. By using a zone, we went straight to the scale starting on its root note; by reducing the number of notes, we were able to shift our focus to crafting phrases and melodies as oppose to blindly running up and down a scale pattern trying to find the music.

The Book

I had a lot of success with this method, so I decided to turn it into a full reference book for 15 of the most useful, and common, scales in any style of music beyond pentatonic scales. In the book, you’ll find the patterns for all five zones by individual zone and all five zones for each scale, giving you the complete picture when it comes to turning scales into solos. Learn more about the book below.

From Scales to Solos – Zonal Improvisation on Guitar

Learn more:

-The Advancing Improviser: Parallel Thinking

-The Problem with Shapes and Patterns on Guitar