13 chords are interesting because they contain the same number of notes as a diatonic scale.

Major 13

If we look at the intervals in a maj13 chord we get:1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13 which is the same as a major scale but as I mentioned earlier, a major scale is usually written out as follows:

1, 2 (9), 3, 4 (11), 5, 6 (13), 7

The logical conclusion here is that you can blow over a maj13 chord with the major scale; and you can, try it with your looper.

I want you to compare the scales method to the chord tones method we’ve been building up in this series. It bears repeating that not all intervals were created equally, and as you may have just realized, running up and down a scale pattern over a maj13 chord doesn’t quite cut it.

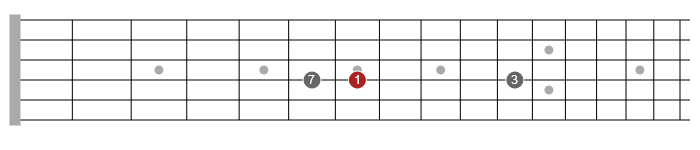

Your base sequence here will be as follows, but you already knew that!

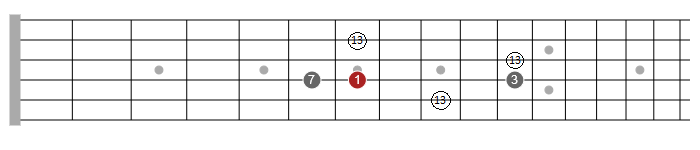

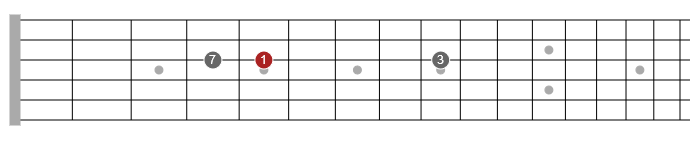

Then it’s up to you to add in the other intervals and see what they sound like. Here’s where you’ll find all the nearest 13s:

Minor 13

A Minor 13 chord gives you the exact same intervals as the Dorian scale:

Dorian Scale: 1, 2 (9), b3, 4 (11), 5, 6 (13), b7

Min13 Chord: 1, b3, 5, b7, 9, 11, 13

Again, try improvising over a Am13 chord with the A Dorian scale, then try by using the following base pattern and adding in the relevant intervals.

Dominant 13

You won’t be surprised to learn that a dominant 13 chord contains the exact same intervals as a Mixolydian scale:

Mixolydian Scale: 1, 2 (9), 3, 4 (11), 5, 6 (13), b7

Dom13 Chord: 1, 3, 5, b7, 9, 11, 13

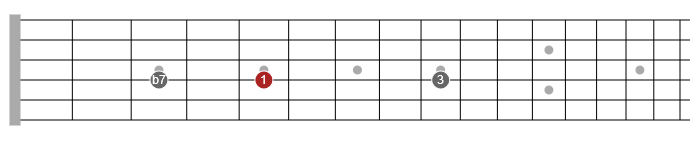

Once more, try improvising over an A13 chord with the A Mixolydian scale, then try using the following base pattern and adding in the relevant intervals.

I’ve purposely left a lot of the diagrams in this series as sparse as possible so that you’re really practicing finding intervals as oppose to memorizing patterns. Remember, there’s nothing to memorize here because what hones your skills is the practice of locating the interval you want to play on the fretboard. You’re probably finding that you need half as many notes as you do when you improvise with scales – this is great for you and your audience because you sound like you know what you’re doing and inevitably more melodic.

Step-by-Step Guide to Playing Over a Set of Changes

If you’ve worked your way to the end this series, congratulations! You should be in good shape to apply your knowledge to any set of chord changes, though I do recommend taking it easy in the beginning.

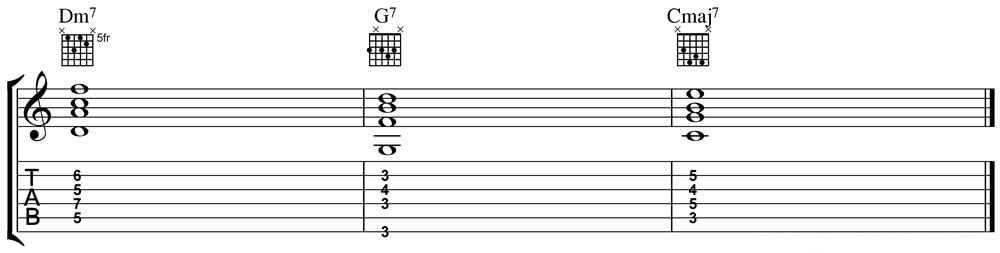

Let’s tackle a set of changes and see what happens. A good place to start is the classic jazz ii-V-I sequence. Don’t be put off by the word ‘jazz’, if you’ve gotten this far, you can do this.

A quick analysis tells us that we have a Dm7 chord (1, b3, 5, b7), a G7 chord (1, 3, 5, b7), and a Cmaj7 chord (1, 3, 5, 7). Our three base sequences could be as follows if we keep them in close proximity:

Dm7

G7

Cmaj7

When you first try this, do it VERY slowly and just use the basic chord tones because what you want to get a feel for first is actually playing the changes and if you go slow enough, you’ll have time to anticipate each chord change.

As you become more comfortable changing between chords, feel free to add in the 5 as well as the upper extensions of the chords (9, 11, 13). Record yourself to see what it sounds like; I guarantee it’ll sound better than you think.

You will feel that this is somewhat mechanical at first as you start to negotiate the fretboard in a different way; what then happens is that your ear takes an interest and will start to make ‘melodic suggestions’. It doesn’t do this that much when you’re blazing up and down scales basically because you’re not relying on it, but when you start to choose what you play, your ear will take an interest. Pay attention to it and see where it takes you as these are glimpses of the ultimate goal here: to play what you hear in your head. You won’t always hear something in your head though, and this is where knowing how to get to certain intervals comes in.

The eBook version of this entire series (Parts 1-8) is now available in PDF format here (pay what you want, minimum $1.00)!