If you’ve been following this series, you’re probably beginning to see how useful a knowledge of intervals coupled with a good ear is, and how much easier it makes navigating the fretboard. If you search online for a guitar lesson on intervals, more likely than not you’ll find some kind of explanation of what intervals are for, then a bunch of patterns showing you where they can be found on the fretboard. While learning a bunch of intervals in isolation sounds like endless fun, I’m going to suggest a more practical approach.

Take it to the Next Level

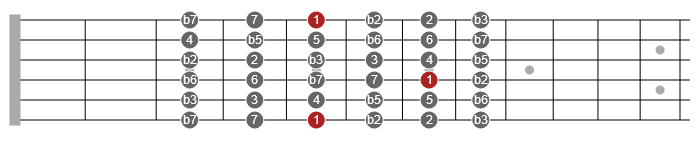

If you already know a bunch of scales, arpeggios or chords, a great thing you can do is gain a deeper understanding of them through intervals. We’ll use the following road-map as our master guide to intervals on the guitar neck for the purposes of these exercises. It’s modeled on the reach of the pentatonic box one hand position, as it’s a comfortable one to start out with.

Use this diagram from the point of view of your first finger on the root on the top E string, and your third finger around the root on the D string. The majority of your soloing should be on the top 4 strings; this is where learning scale patterns and arpeggios from the root on the bottom E string kind of screws you over.

Intervals versus Note Names

When it comes to the guitar, intervals are a lot more flexible than note names. There are 12 keys so there are 12 spellings of everything if you use note names. On the other hand, as intervals are formulas, there’s only one formula for each type of chord, scale or arpeggio. I mean, it’s great to know that a G major chord contains the notes G, B and D, but if you want to move that information around the fretboard on the fly, then it’s easier to do with the formula 1, 3, 5.

Slow Down

You may know the pentatonic like the back of Eric Clapton’s hand but do you ever stop to look at which intervals you’re playing? The Minor Pentatonic Scale contains the intervals 1, b3, 4, 5, b7, but the Pentatonic Scale is also a great springboard to add in other intervals such the 6, the major 3rd, and of course, the b5. You may already do this without realizing but slow down and use the diagram to see exactly what it is that you’re playing. I guarantee it will affect your note choice and phrasing in a good way.

How to Practice

All you need to practice with intervals are a list of formulas like the ones below. Choose one you want to work on and apply the following rule:

Don’t go to the next note unless you know what interval it is.

Check out the following lists of arpeggios and scales.

Arpeggios

Major: 1-3-5

Major add9: 1-3-5-9

Major Sixth: 1-3-5-6

Major 7: 1-3-5-7

Major 9: 1-3-5-7-9

Major7#11: 1-3-5-7-#11

Major 13: 1-3-5-7-9-13

7: 1-3-5-b7

7add11: 1-3-5-b7-11

9: 1-3-5-b7-9

7#9: 1-3-5-b7-#9

13: 1-3-5-b7-9-11-13

Major Sus4 1-3-4-5

Remember: any interval above 7 is written as such because the same interval appears in the next octave. For example, a Major 13 arpeggio repeats the intervals 2 and 4 in the next octave, but they’re written as 9 and 13.

The above list of major arpeggios looks pretty nasty until you realize they’re all basically extensions of a major triad—look at all those 1-3-5s! That’s 13 arpeggios with the same 3 starting notes, 5 with the same 4 starting notes and 4 with the same 4 starting notes. The same applies for minor arpeggios.

Scales

Much the same as arpeggios, you should begin to see that there’s not a great deal of variation in the basis for scales, the thirds and the sevenths being pretty much the deciding factor. I’d recommend looking at the pentatonic major (1, 2, 3, 5, 6), the pentatonic minor (1, b3, 4, 5, b7) and the blues scale (1, b3, 4, b5, 5, b7) from the point of view of intervals, and then the modes of the major scale:

Ionian: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

Dorian: 1, 2, b3, 4, 5, 6, b7

Phrygian: 1, b2, b3, 4, 5, b6, b7

Lydian: 1, 2, 3, #4/b5, 5, 6, 7

Mixolydian: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, b7

Aeolian: 1, 2, b3, 4, 5, b6, b7

Locrian: 1, b2, b3, #4/b5, 5, b6, b7

The idea here is to become aware of what you’re actually playing, rather than learn the locations of a bunch of intervals. If you practice this enough, you’ll start to make conscious choices in your playing instead of just blowing up and down scale patterns. Take it slow and make sure you know the interval you’re going to! There are many more arpeggio and scale formulas which I’d encourage you to experiment with; you’ll like some more than others, and these will become part of your unique style.

-How to Play What You Hear in Your Head (Part 1)

-How to Play What You Hear in Your Head (Part 2)