Check out Part 2 here.

3 and 7 Combinations II

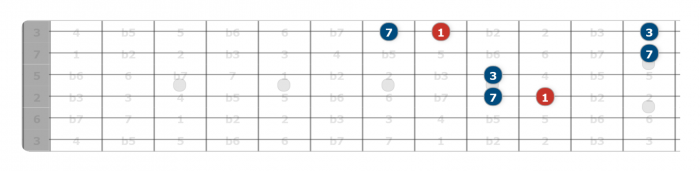

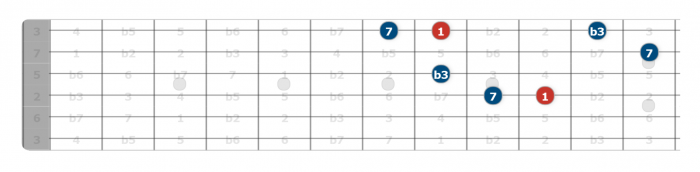

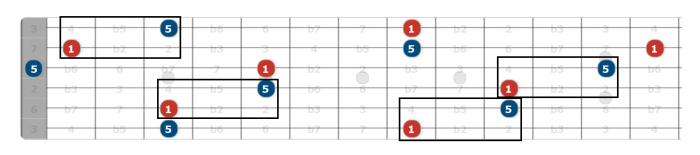

We need to be fluent in recognizing intervals going in all directions on the guitar. Take a look at our 3 and 7 interval combinations again, this time from the top E string.

Again, the idea is not to memorize these as patterns but to know where to find 3s and 7s on the fly and what they sound like in relation to the root note.

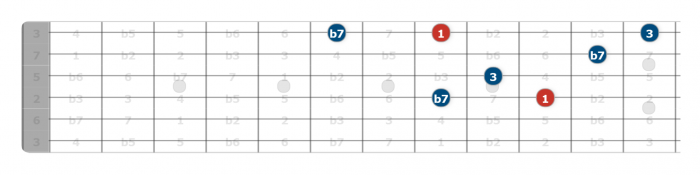

Two Kinds of 5ths

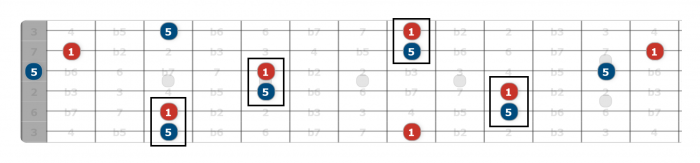

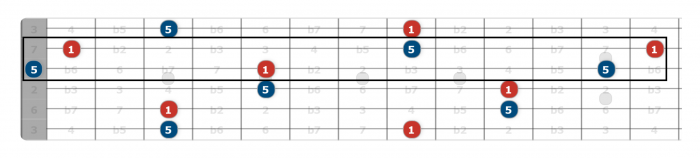

We have two kinds of 5ths available: the perfect 5th and the diminished 5th. You’ll recognize the perfect 5th if you’ve ever played a power chord. Check out where the 5ths are in the diagrams below. We’ll use C as our root again.

There are three things I want you to notice here:

1. The classic power chord shapes.

2. The fact that there is a 5th just below the root on the adjacent string.

3. What happens on the B string.

Basically, due to the guitar’s tuning, the B string shifts everything up one fret. Therefore, we have the same two patterns as in 1 and 2, but shifted up a fret. I find this is the easiest way of thinking about it, rather than thinking of them as new patterns.

The takeaway here then is that you have a 5th above the root in the form of a power-chord, and one below it on the same fret of the adjacent string UNLESS the B string is involved.

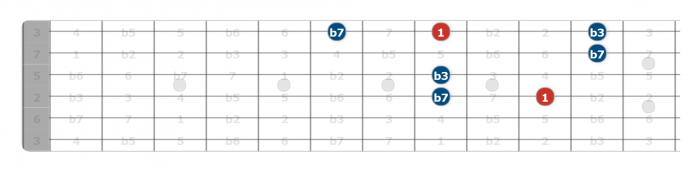

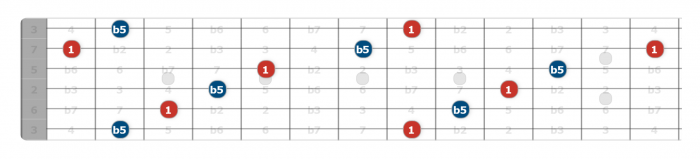

The ♭5 (or ♯4)

A ♭5 and a ♯4 will produce the same note. As a general guide for usage, you tend to use the ♯4 when the 4 is being modified and there’s already a 5, such as in the Lydian scale (1, 2, 3, ♯4, 5, 6, 7), and the ♭5 when the 5 is modified and there’s already a 4, though this is fairly subjective. In a Phrygian scale, for example, you’d write the intervals as 1, ♭2, ♭3, 4, ♭5, ♭6 and ♭7 to keep the numbering consistent.

Here’s where to find the ♭5 on the fretboard:

Again, note that you can always find a ♭5 diagonally above or below the root, EXCEPT from the G string to the B string where the intervals have shifted up a fret.

Once you’ve digested all of that, check out Part 4.