If you’ve been following this series, you can probably guess how we’re going to form eleventh arpeggios. If you haven’t, feel free to check out Part 1 and Part 2 as they’ll provide you with a solid foundation for incorporating arpeggios into your scalar playing or scales into your arpeggio playing, depending on how you’re seeing things. What I love about this approach is that I don’t have to think of a separate pattern for arpeggios and scales or make any drastic changes to my fingering when playing. All the information I need is right there under my fingers, I just have to notice it.

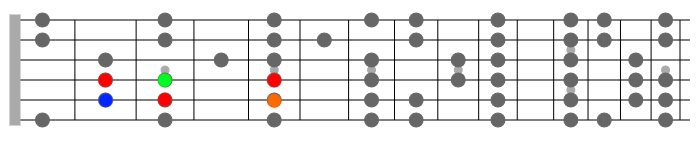

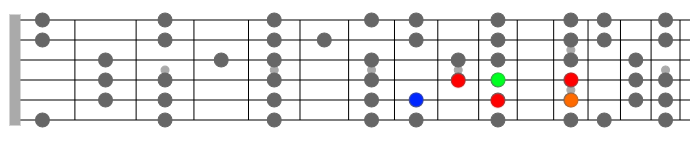

In Part 2, we saw that the 2 is technically the 9 and used it for ninth arpeggios. Here, the 4 is technically the 11 (in green), so we’re going to use it to form diatonic eleventh arpeggios. First up is Cmaj11:

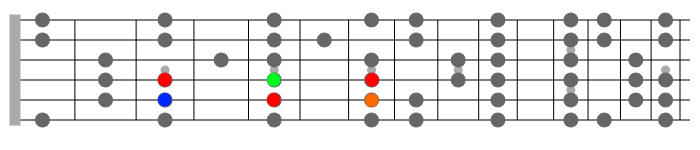

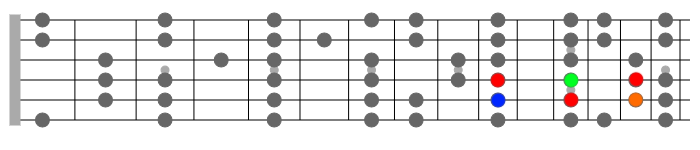

Just to recap, we now have the intervals 1, 2 (9), 3, 4 (11) and 7 only in very close proximity. Next up is Dm11:

Then we have Em11b9:

It’s interesting that playing through arpeggios this way gives you a completely different sound that running scale patterns. Play the three notes in red first, then add in the orange, blue and green notes to hear how the arpeggio builds.

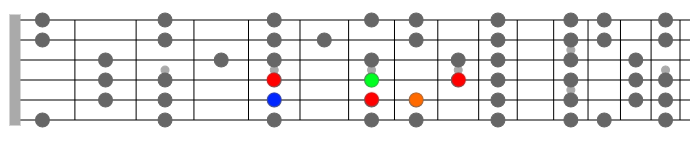

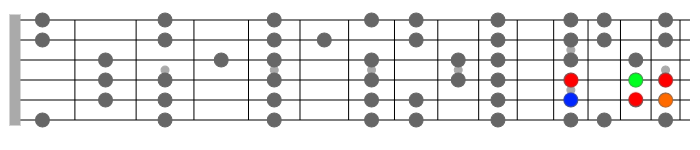

Next up is Fmaj9#11:

I really like the sound of this one; when you play these arpeggios, note that your second finger is always on the root note.

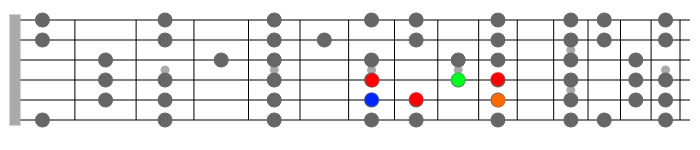

Here’s the G11 arpeggio:

And the Am11 arpeggio:

And finally, the Bm7b5b9 arpeggio:

Remember, you can repeat these patterns across the neck on adjacent string sets as we did in Part 1 and Part 2. The idea here is to help you bring out the melody in a scale, as well as giving you some ideas for playing over chord changes and note choice into the bargain.

What about thirteenth arpeggios?

Glad you asked. The 13 is technically the 6, so if we add one more note to these arpeggios we’ve come full circle and arrived back to a scale! If you wrote out the intervals in a thirteenth arpeggio, they’re the same as those in a scale: 1, 2 (9), 3, 4 (11), 5, 6 (13), 7. More on that here and here.