To check if you’re doing this, you need to watch your fingers intently as you improvise to look for the following tell-tale signs:

-You know the scale all over the fretboard but only use certain parts of it.

-You use the exact same fingering for every run.

-You tend to start out your licks and runs only with your first or (less often) third fingers.

-You run out of ideas quickly when soloing.

If any of the above sounds familiar, you may be trapped by your own fingers, but don’t worry, the following simple exercise can correct this and really open up the fretboard for you.

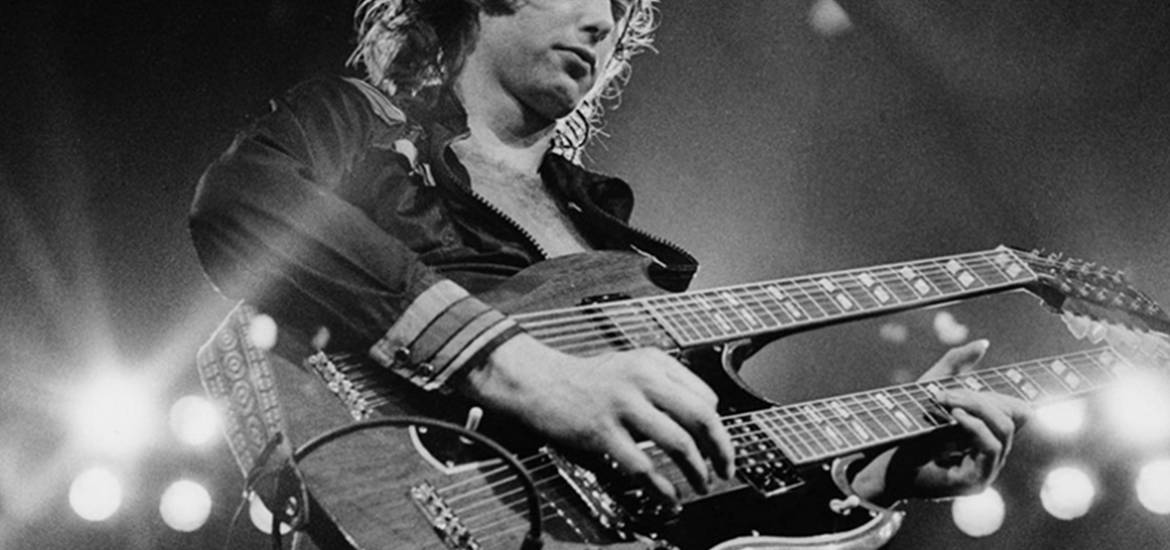

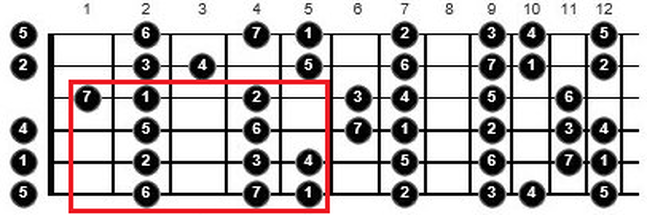

When I ask students to play an A Major scale using the following diagram, they almost inevitably play the 3NPS shape with the root on the low E string, starting on the first finger. There’s nothing technically wrong with this but how useful is this pattern for improvising? The patterns itself locks your hand into that 3NPS-type grip, restricting movement, unless you’re heavily into legato. The pattern should really serve to memorize where the notes are on the fretboard so that you can navigate in and around it with any fingering, as oppose to your hand being locked in that position and just playing the notes that fall under your fingers.

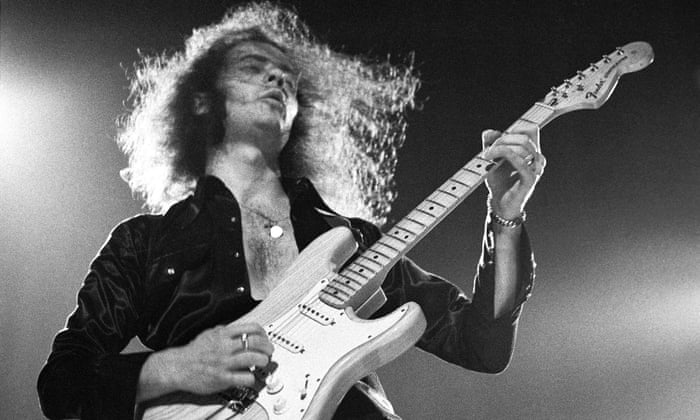

The above pattern is a little more improvisation-friendly, and if you’ve ever learned the CAGED shapes, it should be familiar.

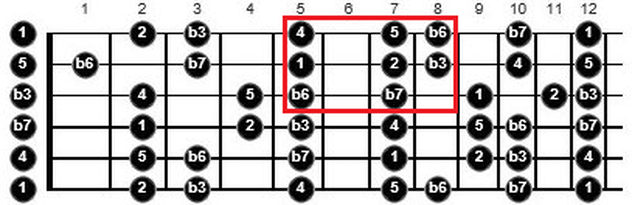

Repeat the exercise again but this time start the pattern on your fourth finger. If that doesn’t throw you off, you should come up with something like the following pattern.

Try this from any available root note, especially the ones on the top three strings; this will greatly improve your freedom on the fretboard, as we shall see below.

Tip #1: Finger patterns should not dictate note choice – it should be the other way around. With whichever finger you start a scale pattern on, you should still be able to find notes and navigate your way around the fretboard.

The Most Important Root Notes

I always find it slightly bizarre that scale patterns are generally taught from the lowest available root note, either on the low E or A strings, and by pretty much everyone. Since most improvisation is done on the top four strings, this seems (to me) to be highly inefficient. This means that a lot of players see scales from the bottom up, as it were, while it’s more efficient to see them as a group of notes with various entry (and exit) points. The most useful entry points (root notes) are on the top three strings.

Test yourself: how many scale patterns can you play from the high E string as oppose to the low one?

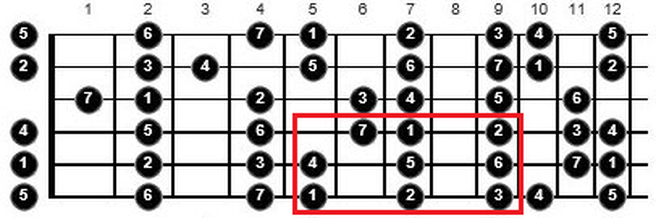

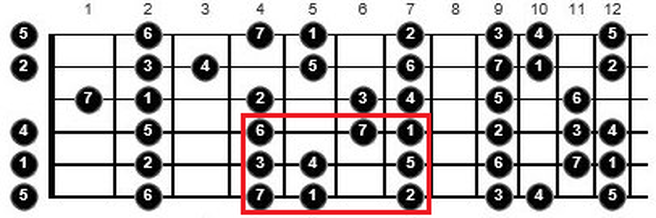

Look at the following diagram. It’s an E Natural Minor scale with the root note on the B string. Clamp your first finger on that root and you have access to all the other intervals in the scale, both above and below the root. This makes for far more musical phrasing than if you were to start the pattern on the low E and A strings. Add slides, bends, hammer-ons and pull-offs and you’re good to go.

Tip #2: Practicing scales will be much more productive if you do it from root notes on the top three strings – top down as oppose to bottom up – as this is the part of neck where most soloing is done anyway, and you don’t want to be lost there.

Quality over Quantity

A lot of players worry about learning a ton of different scales for every situation when just a handful is more than enough. There’s always something new to learn, or some new sound to discover with every scale, so it’s better to know a handful of scales very well, rather than a ton of scales in a hit and miss fashion. This might seem obvious when you think about it, but it works on a deeper level. If you’ve been playing for a while, you probably feel comfortable with the pentatonic and blues scales, and perhaps a few of the modes. This is because you’ve played and explored them enough for the knowledge to become second nature i.e. improvising with these scales feels very natural and almost effortless. I would spend the same time getting acquainted with other very useful scales such as the Dorian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Natural Minor (Aeolian) and perhaps the Melodic Minor scale. Again, the trick here is to work the top four strings as much as possible, as in the Zonal Improvisation approach, and break away from the ‘root note on the bottom two strings’ idea.

Tip #3: A scale (or pretty much any piece of information on the guitar) is only truly useful when it becomes second nature; in other words, you can call on it and use it well without thinking.

Slow is More

I do believe that less is more, as can be heard in the playing of David Gilmour or BB King to name a few, but SLOW is also more. You see, the faster you play, the less likely you are to be improvising because if improvisation is really ‘sped-up composition’, few can compose at such breakneck speeds. It’s only by playing slow, or as fast as you can think, that you gain control over what you’re playing and either pull melodies from your head or at least choose the next note/interval you want to use. Try it for yourself; as soon as you speed up, you either rely on patterns or your improvisation becomes incoherent at best.

Tip #4: Play as fast as you can think if you want to play what’s in your head. If there’s nothing in your head, which does happen a lot of the time, feel free to fall back on the patterns you know – another advantage of knowing them well!