If you’re a fan of fusion improvisation, Wayne Krantz is essential listening, especially live and in the 55 Bar in New York. Wayne is one of a handful of players who are unapologetically themselves, have their own criteria, and are relentless in pursuing they way they think about music. As with other such uncompromising individualists like Allan Holdsworth, Vernon Reid, Frank Zappa, Robert Fripp, Krantz is not hugely popular by the mainstream definition of the word but has a cult following and a great book called, ‘An Improviser’s OS’, (version 2 just released) which you can pick up a copy of here.

I don’t have Version 2 because I need a few more lifetimes with Version 1 due to the mind-blowing nature of probably the only guitar book without a single fretboard diagram in it. You can check out our review of Version 1 here, by the way.

For the uninitiated, the first section of the Improviser’s OS contains every permutation of intervals available on the guitar (that’s 2048) divided into groups of one to twelve notes. The rest of the book is a dialogue with the author about what to do with this information. What makes this one of the most insightful books on guitar improvisation is that it’s exactly how the author thinks about the guitar and music, it’s all laid bare without a single drop of BS.

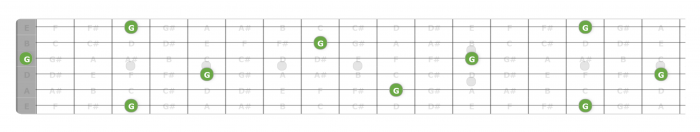

In the book, Wayne suggests you choose a formula (set of intervals) and concentrate a four-fret area of the neck by assigning one finger per fret and improvising using only intervals in the formula that fall under your fingers along to a click while recording yourself. I must admit, I find this difficult to do as my fingers don’t want to stick to one-per-fret and never have done, so what I do is choose a root and divide the fretboard up into octaves as follows (in G).

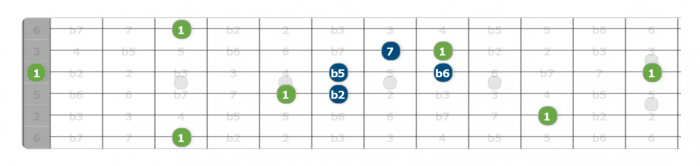

I then choose a formula, choose an octave and see what I can come up with. I like the 4- and 5-note formulas in Krantz’ book as I feel this is just the right number of notes to be dangerous with.

Let’s take a 5-note formula such as 1, b2, b5, b6, 7 and map it out (I do the mapping out in my head when I practice).

The idea is NOT to learn the formula as a scale or something; it’s a means of practicing improvisation, so there’s nothing to remember here. I put on a click and record myself to see what I can come up with using this formula. When I listen back, I’m usually pleasantly surprised that it’s not as shit as I thought it was and that there’s something new/original-sounding in there. Remember that the act of improvisation is the ‘practice’ part, not learning a new formula to whip out during a live solo–this doesn’t really work. I’ll then move the formula around the fretboard to different octaves, which makes you come up with different things.

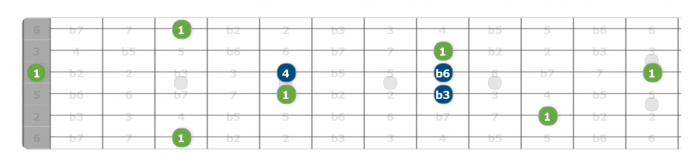

Let’s try it out with a 4-note formula such as 1, b3, 4, b6, which is a lot harder because you’ve really got to be more creative and start thinking about rythmic placement, space, techniques for manipulating notes and so forth; here you can’t avoid those things by playing a lot of notes.

My philosophy here is that when I go to improvise, as well as having nothing in my head, I’ll have practiced going over certain terrain (formulas) and that this will subconsciously come through in my solos. Bear in mind that I’m not thinking in terms of scales (or formulas) when I improvise, and I’m not worried about hitting ‘wrong’ notes either.

I’d really suggest taking this concept for a spin, especially if you’re stuck in a scales rut or are looking for some advanced material to work on.

Pick up a copy of the Improviser’s OS Version 2 here. If you’re an intermediate guitarist looking for a softer approach to work up to this, you might like our Intermediate Guitar Scales Handbook.