Strangely enough, it’s a fundamental part of music but a great deal of guitar music education, and especially guitar books, are not based on it. Whatever style of music you play, this concept is essential to organizing and understanding its structure and what you can add to it in the form of improvisation, chords, arpeggios etc.

It is of course: KEY SIGNATURES, or diatonic harmony, or functional harmony, which are all tantamount to the same thing. When you play a piece of music, 99% of the time you are inevitably playing in a key, be it major or minor, so why is most guitar teaching material not structured this way? This is especially essential learning for high-beginner to intermediate guitarists who know a good selection of chords and scales down but have this kind of ‘scattered knowledge’ where they’re lacking the underlying concept that ties them together: key signatures.

Back in the day

I remember this stage in my learning very clearly because I would often end up jamming with people that were way better than me (another surefire way to take your playing to the next level and get rid of your ego), and someone would say, ‘okay, let’s jam in C and see where it goes’, the bass player would lay down a groove and it was up to me to come up with something. Another scenario would be jamming over a chord progression or tune – and in both situations, if you’re not aware of what the key you’re playing in has to offer, you simply don’t have the knowledge the play anything past the basic changes. I remember the chord progressions going around and around while I desperately tried to calculate what scales, arpeggios, or other chords I could use to play something other than the three barre chords that were starting to give me RSI. What finally gave me that knowledge was learning about key signatures and their contents, then mapping it out on the fretboard.

The Problem with CAGED and 3NPS

A lot of guitarists learn the 5 CAGED patterns or the 7 3NPS scale patterns (should be three) in isolation in a couple of keys, then wonder why they have little or no use for them in their playing aside from a handy technical/picking/warm-up exercise. This is because they lack the context for those scales (the key signature), which tells you how and where to apply them. It’s a little like driving a car with no motor – you can only get so far by freewheeling. In other words, knowing however many patterns for a G Major scale only really comes into its own when you know the chordal, pentatonic, arpeggio, and modal possibilities that go with it.

What to do about all of this

So, if you happen to know, say… the C Major scale thanks to the aforementioned 3NPS or CAGED patterns, what you need to do is learn the context for that key/scale to be able to use it to its fullest potential next time someone decides to have jam in C, or has a chord progression in C (or A minor – the relative minor).

What to learn (summary chart below)

Bear in mind that we’re only scratching the surface here, but I’d consider these a good place to start:

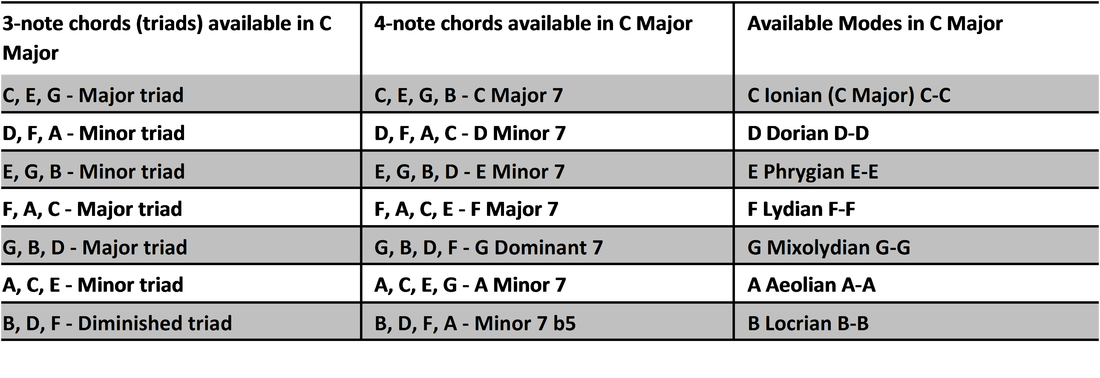

Start with the interval construction: All major scales feature unaltered intervals, that is, the 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 (root, major 2nd, major third, fourth, perfect fifth, major 6th, major 7th) based on their distance from the root. You’ll get these intervals by playing the 1 plus any other note from the key. Playing two notes together is known as a dyad, or in guitaristic terms, a double-stop. You’ve probably been playing the 1 and the 5 together ever since you picked up the guitar because this is also known as a power chord.

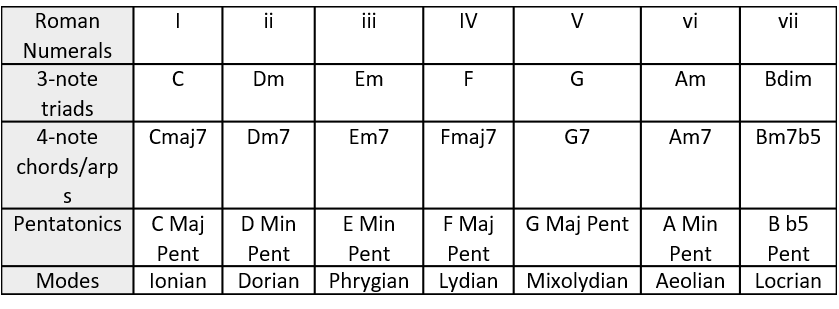

Next, move on to three-note constructions: Three-note constructions are usually known as triads and you can work them out by stacking every other note in the key. For example, in the key of C Major, we have the notes, C, D, E, F, G, A. If I stack C, E, and G I get a C Major chord/triad, if I stack D, F, and A I get a D Minor chord/triad, and so on (here’s how to map them out on the fretboard).

Arpeggios/7th chords are up next: If we stack another note onto our triad we get all the 7th arpeggios/chords in a given key (here’s a great way to learn all the 7th chords), I’ll come to arpeggios in a second.

5-note magic: Did you know that the major scale also spawns the major and minor pentatonic scales?

Modes: The dreaded modes are far easier to understand from the point of view of key signatures, rather than as a bunch of isolated scale patterns. Check out the handy table below which summarizes this and the above concepts.

I’m sure you can already appreciate that there are a ton of things you can bring to a jam in C Major, or any key for that matter since this information is the same in all keys, only the note names change. To really be able to use this information in a jam though, it needs to be second nature, that is, you need to able to find it on the fretboard without thinking.

Moving it onto the fretboard

If you followed the above links, you’ll find they focus on the chords in the key. As far as improvisation goes, there are several ways you could do this, but the important thing is to see how these concepts connect and overlap each other on the fretboard. To give you an example, we’ll work backwards from the scale pattern and what we can extract.

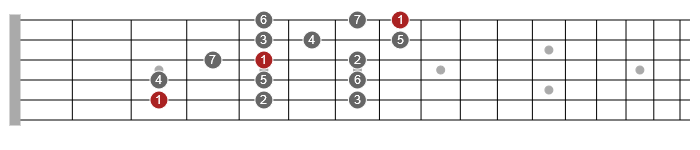

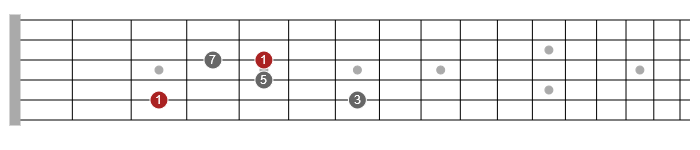

So, here’s a classic C Major 3NPS pattern you probably know well.

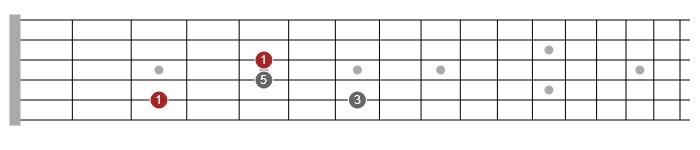

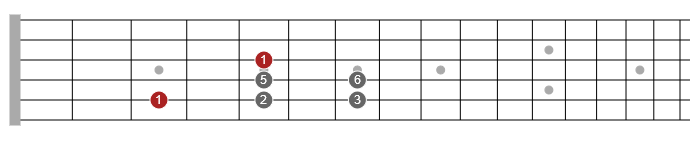

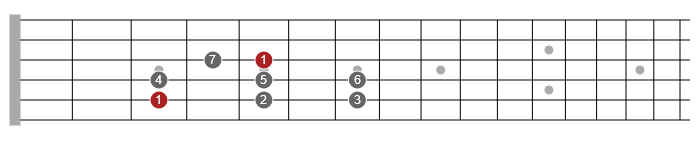

Let’s break it down and focus on just the first octave of the above scale and say we’re soloing over a C Major chord or a progression where the diatonic harmony implies the C Major Scale. These would be our improvisational tools in one position:

C Major Triad Arpeggio (C, E, G)

C Major 7 Arpeggio (C, E, G, B)

C Major Pentatonic (C, D, E, G, A)

C Major Scale (C, D, E, F, G, A, B)

They’re the same notes as the two-octave scale pattern we started with, only now we’re bringing out and really highlighting the different sounds that are in the scale. Don’t worry too much about learning these patterns as just by practicing them, they’ll inevitably start to show up in your soloing because you’ll gravitate toward certain notes and no longer just run up and down scale patterns. Use the chart below to work out the rest of the patterns for the other chords, arpeggios, and scales in the key of C. You can even use the same pattern we started with above.

What you can also do here is find the above patterns in the next octave (the notes will be displaced because of standard tuning), then join the two octaves together. I guarantee that if you practice like this for a while, the way you see and play the scale will change for the better.

To end with, here’s a summary of what we’ve extracted from the key of C Major:

Isn’t there a book I can get to learn all this?