In hindsight, beginners should probably learn triads first, that way it’s far easier to make the connection between open chords, barre chords and triads themselves. In fact, learning an open chord or barre chord is like memorizing a phrase in another language; you can use it in the right circumstances and you’ll be understood, but you have no idea how it’s formed and therefore can’t make your own phrases (chords) outside of that structure. This can easily be solved by learning triads first, then applying that knowledge to open chords and barre chords.

Triads First

A triad consists of three notes and can be major, minor, augmented or diminished. In this lesson, we’ll be dealing with major and minor triads only.

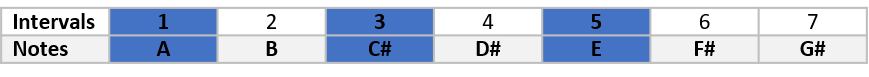

All major triads contain the intervals 1, 3, and 5, so an A Major triad contains the notes A, C#, and E.

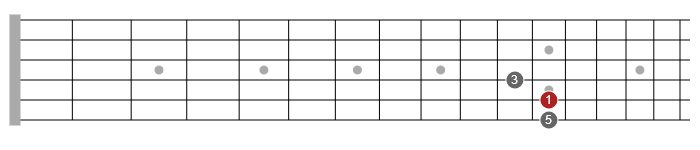

We can get this information from the A Major scale (or any major scale):

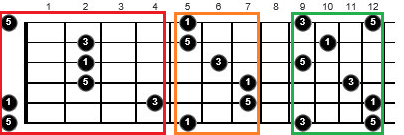

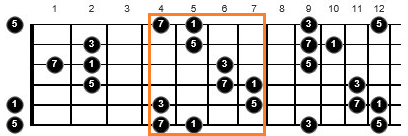

If we put this information on the fretboard, you should be able to see that the A Major open chord (in red) is made up of major triads. When you play a standard A Major open chord, you’re playing two roots (1), two fifths (5) and one major third (3). The low open E string is part of the chord but is not usually played because it’s not a pleasing sound (try it yourself) in this position. What I want you to see here is how major triads are arranged to form major chords. In orange we have an A Major barre chord with much the same weighting of intervals as the open chord, the only difference is that here we have three roots (1), and a different sound due to the distribution of the triads.

In green we have another A Major chord. In this one the notes on the low E string are usually omitted, as well as the 5 on the high E string. This leaves us with two roots (1), two thirds (3) and one fifth (5).

For more on triads check out: How to Learn Triads Faster

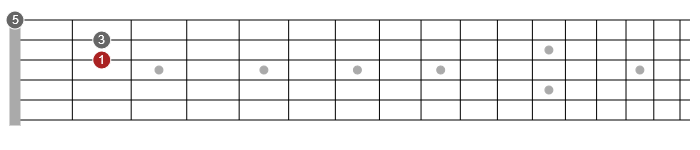

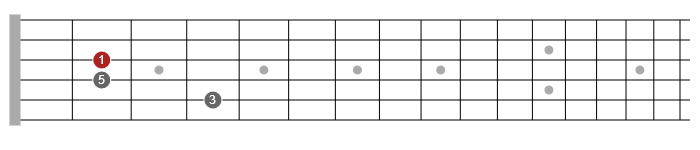

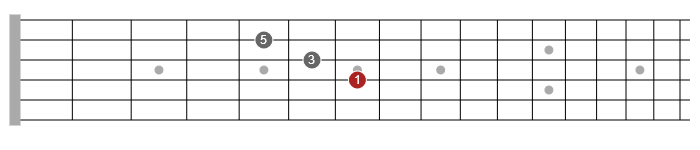

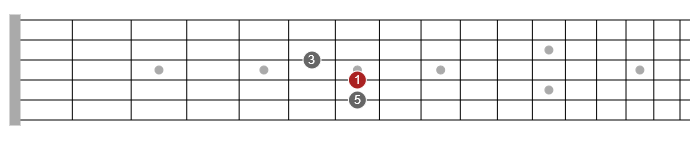

If we break these chord shapes down further, it’s easy to see where the triads fall and how we could even add variations to these chords. Here are the triads that make up our open A Major chord:

So, instead of just playing an open A Major chord, you can add in and omit notes to get different sounds by using the triads above.

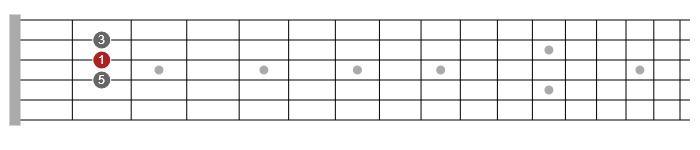

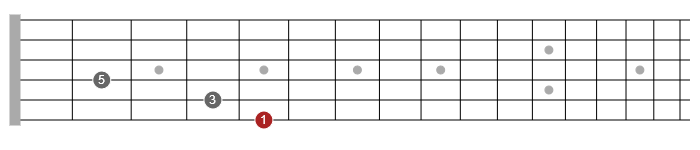

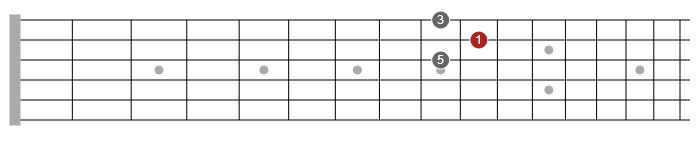

Here’s what happens when we break down the barre chord:

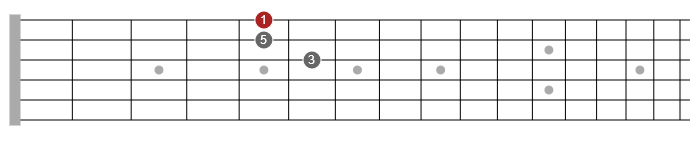

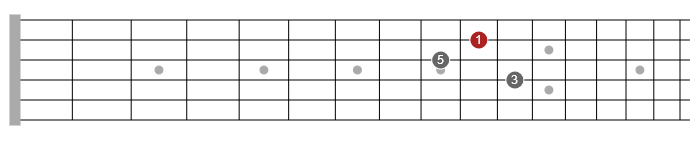

And if you haven’t worked it out already, here are the triad for the third chord shape:

These three sets of triads give us all the major triad shapes available on the guitar neck. You may have already been using some of them, especially on the top four strings, the others should help you to complete the picture or fill in the gaps.

Interval Magic

The major triad alone forms the basis for a vast number of chords, which is why it’s easier to build up a repertoire of chords by knowing how to form triads and add intervals to them, rather than trying to memorize hundreds of chord shapes.

For example, if you know that an A Major 7 chord contains the intervals 1, 3, 5 and 7, and you can find your major triads, all you need to do is locate the 7 (G# in this case) on the neck and add it to the triad. You may have to shift the notes around to get a comfortable fingering, but this is an invaluable process that frees you from relying on memorizing chord shapes (phrases in a language).

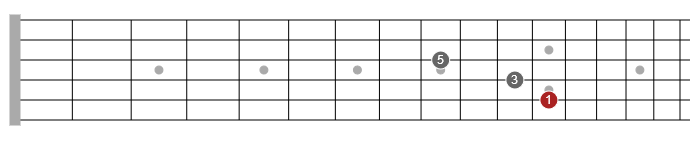

Here’s our A Major barre chord shape again with the location of the 7s around it. Can you pull out the triads and add those 7s to them?

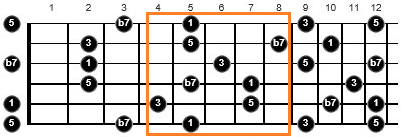

Try doing the same to create A7 chords. An A7 chord contains the intervals 1, 3, 5 and b7

Again, you should see the major triads and be able to find ways to combine them with the b7s within easy reach.

In Part 2, we’ll look at minor triads.