A student once asked me if there was a foolproof way not to get lost when soloing on guitar and as I didn’t really have a magic bullet answer, I thought I’d get into it in this article. There are many ways you can get lost when improvising: you might be in the wrong key, or a chord that’s not in the key might throw you off, you may not know what scale to use, you need to use something other than a pentatonic scale, or you’re trying to fit everything into a pattern or box shape and it’s just not cutting it. What’s more, when you do get lost on the fretboard, you have a couple of choices…

You either use your ear (and discover how underdeveloped it is) or attempt some massive theory calculation on the fly. While it’s always good to have some idea of how you’re going to approach a solo beforehand, it’s not always possible, especially in a jam situation.

But I know my scales…

I know you do… but scale patterns don’t automatically translate into the ability to improvise fluidly over chord changes; in fact, they’re one of the furthest things from it. What I’m saying is that if you practice scales as patterns thinking that they’re the key to a jaw-dropping solo, you might be disappointed. What you ideally want do is expand your scale practice into making that information musical as quickly as possible; this won’t happen any time soon if you’re learning 5 or 7 patterns per scale.

What I’d like to do in this lesson is break things down even further to give you a foolproof way not to get lost when you’re improvising over a set of chords, and it doesn’t matter whether it’s a progression you can blow over with one scale or not, these two simple things will make your solo sound like you know what you’re doing.

Know Thy Progression

The first is quite obvious but most guitarists ignore it – you have to know the chords you’re soloing over. What’s more, you have to know which chord you’re playing over at any point in the tune i.e. ask yourself, ‘what chord am I playing over right now?’ If you don’t know the answer, you’re probably lost or about to be.

The second reason you might get lost when improvising is: you have no idea what the thing you’re about to play is going to sound like. While this might seem like a contradiction in terms because it’s improvisation after all, think about when you play blues or use pentatonic scales; if you’ve been playing for a while, I’ll bet you have a pretty good idea of how what you’re about to play is going to sound. This, in turn, allows you to take a line or a motif and develop it, it allows you to use phrasing to communicate your ideas and generally makes for a coherent solo because you pretty much know what it’s going to sound like when it comes out – there are no surprises.

This skill somehow gets lost when guitarists start using other scales such as the modes – suddenly they’re learning these huge clunky patterns all over the neck and trying to solo with them, only now it sounds like the guitar version of some plate-spinning act rather than the sophisticated phrasing you were able to pull off with the pentatonic scale.

Why does this happen?

With the pentatonic scale, you have five great notes at your fingertips and pretty much all of them sound good. Only hanging on the fourth too much will make you sound a bit lame but all in all the pentatonic scale is pure gold. With other scales, however, the game changes because not all the notes in a 7-note scale, for example, were created equally. This means you won’t get away with staring up to the heavens and wailing away as you did with the good old pentatonic scale.

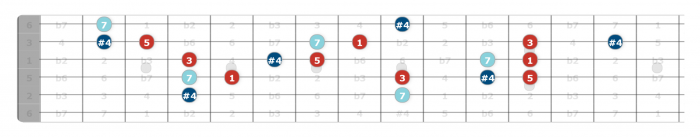

Let me show you what I mean using the Lydian scale. The intervals we’re dealing with here are:

1, 2, 3, #4, 5, 6, 7

Again, not all the notes in the Lydian were created equally and what we’re interested in here to start with is the interplay between the 1, 3, 5 and the #4; the major triad plus the #4. This is the essence of Lydian. You’ll hear people say, ‘oh, the Lydian mode is just a major scale with a #4’, or something to that effect. While this is true, I’d rather you see it as, ‘the Lydian scale is the interplay between the major triad, the #4 and the natural 7’. This gets you thinking about the intervals it contains, rather than treating it as a major scale with a swapped-out 4.

Here’s how it looks on the fretboard:

Here you have three major triads (in red) and the all the #4s and 7s close by. Play around with just these notes and see what you can come up with. You should hear the very obvious-sounding Lydian vibe come through. Compare this to playing the Lydian scale as a 3NPS or CAGED pattern up and down the neck.

The Lydian scale sounds great over major, major 7 and major 7b5 chords. If you want a chord progression to go with this try looping G to A major.

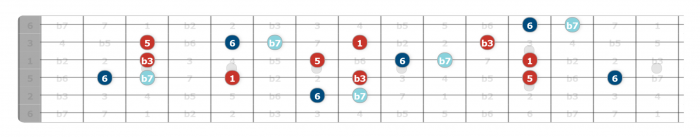

Let’s try the same thing with a minor scale: Dorian.

The Dorian scale is quite subtle and really benefits from an exercise like this to bring out its sound. Here the critical intervals are the minor triad (1, b3, 5) plus the natural 6 and a flat 7; this is the essence of Dorian.

Here it is on the fretboard:

Do the same as we did with the Lydian scale; the minor triads (1, b3, 5) are in red. The Dorian scale works well over minor, minor 7 and minor 6 chords. For chord progressions try looping Gm7 to C or Gm7 to Am7.

Recap

So, what we’re essentially doing here is bringing your ear up to speed so that when you venture into these scales, instead of getting lost, you’ll have some idea of what you’re about to play and whether it’ll work or not.

If you enjoyed this way of learning scales, you might want to check out our book Melodic Soloing in 10 Days, which builds on what we’ve learned here.