If you haven’t read Part 1, check it out now as it builds the foundation for what we’re about to see in Part 2.

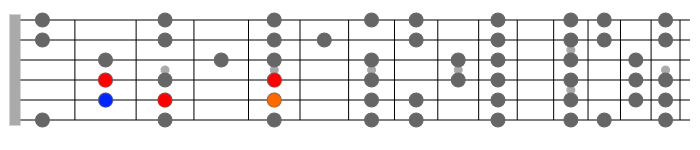

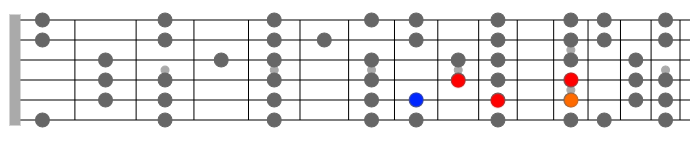

For the diatonic ninth arpeggios, all we need do is add one note (in orange) to each seventh arpeggio pattern. Here’s a Cmaj9 arpeggio:

The note in orange is technically the second, which is also the ninth, but if we add it here we can keep avoiding those etude-style patterns.

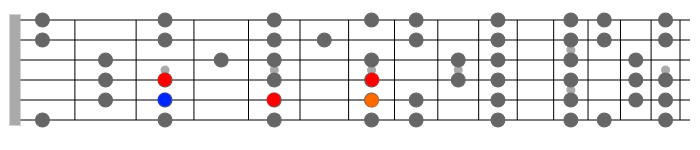

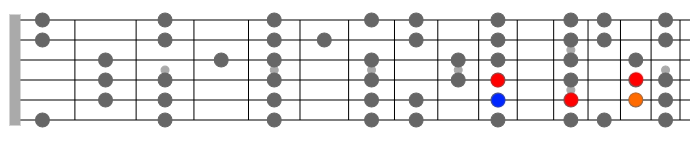

Next up is the Dm9 arpeggio:

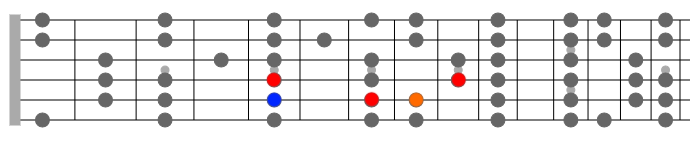

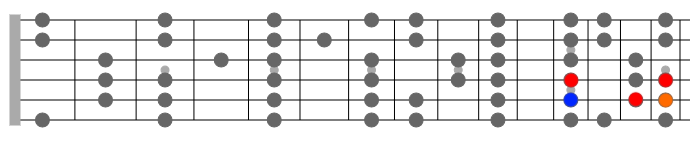

When we shift this up to E, we get an Em7b9 arpeggio:

This is due to the semi-tone between E and F which creates a b9 instead of a regular 9, or in other words just like the 7 and b7 we have the 9 and b7. If we add a 9 to a chord seventh chord, as above, we get Cmaj7 > Cmaj9, Dm7 > Dm9, but if we add a b9 we get Em7 > Em7b9. As we shall see, the same happens with the Bm7b5 chord.

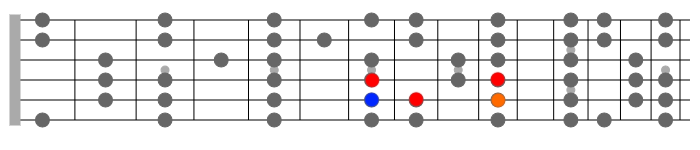

Next up is the Fmaj9 arpeggio:

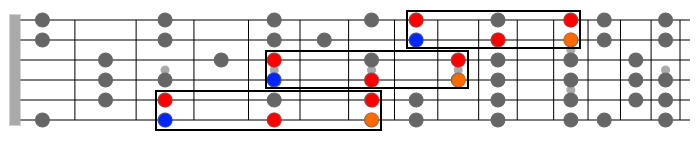

Remember you can move these patterns around the fretboard and join them up to form extended ones as we did in Part 1.

Here’s the G9 arpeggio:

The Am9 arpeggio:

And finally, the Bm7b5b9 arpeggio which also features that b9:

Are these really arpeggios?

In the sense that they’re usable patterns that contain the notes of the requisite arpeggio, then yes, they are; in the sense that they make that gloop-gloop arpeggio up and down etude sound, then no, they’re probably not. The idea here is to pull arpeggios out of scale shapes in a way that’s almost like ‘highlighting’ as oppose to a clunky pattern which is often difficult to find and incorporate into your playing. If you’re missing the ‘shred’ element, try linking the patterns together as in this Am9 arpeggio which goes from the third fret right across the fretboard and up to the twelfth:

In Part 3, we’ll be looking at eleventh arpeggios… but you can probably already guess how those are formed.