Music takes place over a set amount of time. A piece of music isn’t just a bunch of chaotic notes. It has a beginning that works its way, measure by measure, to an end. As such, one of the most essential skills for a guitarist to master is the ability to keep time. A poor sense of timing can leave you lost in the piece and will turn a great song into a hot mess.

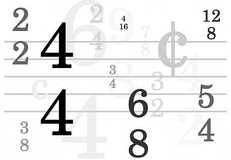

Each measure of music receives a specified number of beats. A time signature, or meter, is what tells you how a song is to be counted (not to be confused with tempo, or the speed at which the song is to be played). It is written at the beginning of the staff after the clef and key signature, and consists of two numbers written like a fraction. The top number of the time signature (the numerator) tells you how many beats to count per measure. Most often the number of beats will fall between 2 and 12. The bottom number (the denominator) tells you whether to count the beats as quarter notes (4), eighth notes (8), sixteenth notes (16), etc.

The most common time signature in music is 4/4. It’s the time signature of choice in most rock, blues, country, funk, disco and rap music. A 4/4 time signature means you count four (top number) quarter notes (bottom number) to each measure. However, it doesn’t mean that each measure has only four quarter notes. It means each measure has only four beats. These beats may contain half notes, quarter notes, eighth notes, rests, whatever the composer wants, but all note and rest values must combine to equal no more or no less than the top number of the time signature.

Because it’s so common, 4/4 is actually called common time and is often marked with a “C” instead of 4/4. It means the same thing. (One other time signature abbreviation is cut time, or 2/2. Cut time is usually written as a “C” with a line through it.)

For songs in 4/4 time, you would count four beats to a measure, or 1 2 3 4, 1 2 3 4. If you are playing eighth notes in this meter, you insert an “and” in between the quarter notes and count 1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and. You can further subdivide the beat into sixteenth notes by inserting an “e,” as in 1-e-and-a, 2-e-and-a, 3-e-and-a, 4-e-and-a). You can continue to subdivide to even faster beats though they may become harder to count out loud.

Notice how the pattern of 4/4 meter creates an emphasis on beats 1 (the stronger accent) and 3, which are downbeats. Beats 2 and 4 are upbeats. In many rock, R&B, and hip-hop songs, the upbeats are accented. This is commonly called a backbeat.

The second most popular time signature is 3/4. Most commonly known as a waltz meter, 3/4 time is also used in country western ballads, rock songs, and various other genres. A 3/4 time signature means you count three quarter notes to each measure, or 1 2 3, 1 2 3. In 3/4 meter, beat 1 of each measure is the downbeat, and beats 2 and 3 are the upbeats. It’s quite common, though, to hear accents on the second or third beats, like in many country music songs.

Another common time signature is 2/4. Divide a 4/4 meter in half and you’re left with only two quarter note beats per measure. Most famous marches are composed using 2/4 timing. The rhythm is similar to the rhythm of your feet when you march: 1 2, 1 2 (left-right, left-right).

Okay. So you’ve got common meters down. But what if you’re getting tired of the same old time signatures? What to do if your songs are starting to sound a bit too predictable, and maybe you’re just a little bored playing the same beats all the time. If this is the case, then maybe you might want to expand the boundaries of your musical expression by trying out some odd meters.

Odd time signatures are challenging but can add a whole new level of interest to your music. Avant-garde genres such as jazz and progressive rock frequently make use of unusual time signatures in order to move beyond the normal confines of popular music.

Let’s begin with 5/4 timing, which calls for five quarter note beats per measure. They can be counted as 1 2 3 4 5, 1 2 3 4 5. But an odd time signature can be simplified by breaking it down into smaller, more common units. For example, a 5/4 signature can be decomposed into 3/4 + 2/4, meaning you count 1 2 3 1 2 instead of 1 2 3 4 5, emphasizing beat 1, or the downbeat. You could also reverse that and count 2/4 + 3/4, or 1 2 1 2 3, again with emphasis on beat 1. Listen to the difference in sound between the two examples. Meter is the one case where 3 +2 doesn’t equal 2 + 3 due to the emphasis (the accent) placed on the downbeat. You can get very imaginative when breaking the rhythm down. Now try 5/4 as 1 2 3 4 1.

Let’s look at 7/4. You can count this meter out as 1 2 3 4 5 6 7, or you can break it into 4/4 + 3/4 timing and count 1 2 3 4 1 2 3. You can also divide it out to 3/4 + 4/4 (1 2 3 1 2 3 4) or even 2/4 + 2/4 + 3/4 (1 2 1 2 1 2 3), accenting beat 1.

What about 10/4? You can break this meter down in multiple ways. For example, 5/4 + 5/4 (1 2 3 4 5, 1 2 3 4 5), which then can be broken down to 3/4 + 2/4 + 3/4 + 2/4 (1 2 3 1 2 1 2 3 1 2). Or you can play 10/4 as 4/4 + 4/4 + 2/4 (1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2), again accenting beat 1.

How would you play in 11/4? Well, you could break this odd meter down to 4/4 + 4/4 + 3/4 (1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3), or 3/4 + 4/4 + 4/4 (1 2 3 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4), or 4/4 + 3/4 + 4/4 (1 2 3 4 1 2 3 1 2 3 4), or even 3/4 + 3/4 + 3/4 + 2/4 (1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2), emphasizing beat 1. You get the picture.

You won’t come across unusual time signatures too often, but when you do, they can be the most recognizable pieces of music you’ve heard: “Solsbury Hill” by Peter Gabriel (7/4), “Money” by Pink Floyd (7/4), “Say a Little Prayer” by Burt Bacharach (10/4 and 11/4, as well as measures in common time), “All You Need Is Love” by the Beatles (7/4, 4/4 and 6/4), and the theme songs from the films Halloween (5/4) and Mission Impossible (5/4), to name a few.

A whole other level of complexity can be explored by working with these and all the many other unusual meters available to you, like 12/8 and 4/16, so roll up your sleeves and dig in. The more you play around with odd time signatures, the more they will become second nature to you, and the more interesting your sound will be as a result.

For more on how time signatures work, see Intro to Timing and Rhythm in Music.

Kathy Dickson writes for guitartricks.com, which offers online guitar lessons for beginners.