When you come to write your own material as a solo artist, band member, composer, or anything else, you’re going to need to know which chords belong in which keys. Even if you plan on ignoring all the rules and creating a dissonant, atonal masterpiece – you need to know the rules before you can break them. Assuming you’re already able to play a few chords with a solid technique and you’re starting to know your way around the fretboard a little, here’s a lesson on how to know which chords belong in which keys. At first, this may seem like a long-winded process, but I can assure you from working through it with many of my students, that with a bit of practice, the process speeds up and before long, you’re doing it in no time at all.

Step 1: Which Key Are You In?

The first thing to do

is to ensure you know which key you’re in. This is nearly always the

first chord of the song (and very often the last, too). Other ways to

deduce a songs key are to look for the note or chord that feels like

‘home,’ where the chord pattern resolves or comes to rest, or if you’re

familiar with your pentatonic scale, to try playing it over the song in a

few different places, searching for where it feels and sounds right.

Step 2: Relative Major/minors

If

you find in Step 1 that you’re in a minor key, say A minor, or C minor,

(or any other), then the first thing you’ve got to do is find its

Relative Major key. If you don’t know what this means yet – essentially,

keys go together in pairs of one Major and one Minor. These pairs of

keys are said to be “Relatives” – i.e. every Major key has a relative

minor key, every Minor key has a relative Major key. To find a Major

key’s relative minor, go down 3 frets (or ‘semitones’ – see step 4). To

find a minor key’s relative Major, go up 3. And there you have it!

Before

progressing onto the following steps, you must have found the

appropriate Major key. So, if you find you’re in A minor, go up 3 frets

to find the relative Major of C Major. Or if you’re in B minor, go up

the 3 frets to find the relative Major of D Major. This is because all

basic music theory is discussed in terms of the Major scale. You can

start to think of keys in pairs now – the key of C Major / A minor, or

the key of D Major / B minor, and so on. Both are formed of precisely

the same notes and chords, and it’s only where you place the emphasis

that determines whether the key is simply referred to as one or the

other.

Step 3: What’s the ‘Parent Scale’?

The

Parent Scale is the scale upon which a key is formed and named. Put

simply, if you’re in the key of C Major, the parent scale is the C Major

scale; if you’re in the key of Eb Major, the parent scale is the Eb

Major scale. If you know which key you’re in, you know which scale

you’re using. As per Step 2 here, if you’re in, say, A minor, the parent

scale you need to find is that of the relative Major – C Major. Always,

always, relate back to the Major scale at the heart of it all!

Step 4: Make the Scale

Now

that you know you need to find, say, the C Major Scale, or the Eb Major

scale, let’s make the scale. If you don’t know how to do this, there’s a

formula, which works for every Major scale: it’s all about the steps

between the notes. If you’re not already, get familiar with the concept

of a “semitone” and a “tone.” A semitone is the distance from one

musical note to the next, or one fret on your Guitar. A tone is two

semitones, or two frets on your guitar. The formula for a Major Scale is

simply a combination of tones and semitones, as follows:

T T S T T T S

So,

from the note of C, we go a tone to D, another tone to E, a semitone to

F, and then tones to G, A, then B respectively, creating the C Major

Scale:

C D E F G A B

Using the same formula for the Eb Major Scale:

Eb (t) F (t) G (s) Ab (t) Bb (t) C (t) D (s)

There’s

a bit more detail in the above step, so if you’re at all unsure, read

over the section again, then test yourself by attempting to form and

write out some Major scales I didn’t cover above, like F Major, D Major,

Bb Major, and so on. Then look them up and check you’ve got them right.

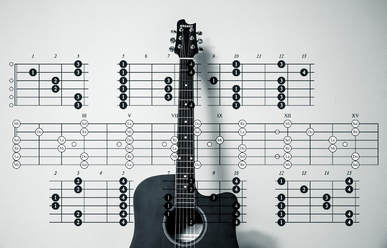

Step 5: Turn the Scale into Chords

Again,

there’s a formula, so don’t panic. You need to get this formula to

stick in your head as soon as you can, so get to work on that. In any

Major key, chords 1, 4 and 5 are Major, 2, 3 and 6 are minor, and 7 is

diminished. No matter what – this always applies.

The formula is:

IMaj IImin IIImin IVMaj VMaj VImin VIIdim

So, in C Major (or A minor):

CDmEmFGAmBdim

And

there you have it – there are the 7 natural, inherent chords in the key

of C Major and A minor. Not to say that you won’t find this rule being

broken all over the place, as we discussed earlier, but it’s important

to know. Whether you’re trying to figure out a song’s chords by ear and

want to avoid pure trial and error which is inaccurate and

time-consuming, or you want to write some music and need to know which

chords are going to work well in your chosen key, or you want to break

the rules but therefore still need to know them in order to do so, this

is a super important tenet of basic music theory.

Remember that

music theory should be an ever-broadening horizon, as you learn a

little bit more, piece by piece. You don’t need to understand EVERYTHING

right now, just work with what you have, and gradually develop your

knowledge, always applying it to your playing and composing.

Enjoy, and good luck!

Alex Bruce writes for GuitarTricks.com.