You’ve reached the turning point!

If you’ve been practicing the material in the previous parts, and depending on how long you’ve been playing, you’ll most likely have to fight with yourself NOT to revert to patterns and mindlessly running up and down scale patterns or going over licks you often play. I don’t want you to get rid of this area of your playing because I imagine you’ve spent years crafting it, and it probably works for you to a certain extent. What I do want you to do is to start making the conscious shift to choosing the intervals you play and breaking out of the confines of any pattern you may know. I’m sure you know the feeling: you’re hacking your way through a solo or chord progression and wondering what you could be doing to make it more interesting, what other options there are, and above all, to have more control over it.

What does ‘knowing the fretboard actually’ mean?

To me, ‘knowing the fretboard’ means being self-sufficient where chords, arpeggios, scales and their corresponding interval structures are concerned. In other words, you don’t need to rely on knowing the scale/arpeggio pattern or chord shape to be able to play it, and this is the problem with patterns and shapes: you either know it or you don’t, and if you don’t, you’re screwed.

Let’s say someone puts a progression in front of you and you know a shape for each chord except one, an Am6; what are you going to do if you don’t know the intervals for a m6 chord, or at least the notes? If you know that a m6 chord contains the intervals 1, ♭3, 5 and 6, then you can make your own m6 chord anywhere on the fretboard. What’s more, you can play all the other chords anywhere on the fretboard you like because you’re not relying on knowing a couple of shapes in random positions. If you’re jumping around the fretboard playing only the shapes you know, your progression will sound a bit lame.

What about the shapes I already know?

As I said, don’t worry, you don’t have to ‘undo’ any of these because you’ve already internalized them. What you will be able to do is analyze them and understand them a bit more, as well as where they fit in the grand scheme of things.

Gently does it

I won’t lie, this does require a huge effort on your part, but you know deep down that patterns and shapes are holding you back.

Don’t worry, we’re going to go at this gently as this will take a while to absorb, though you should have a lot of light-bulb moments along the way.

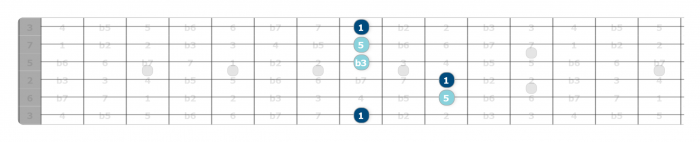

Let’s say someone’s playing a straight minor chord, like the one below, you have a variety of options as far as intervals are concerned.

Basically, we have the intervals that are chord tones: (1, ♭3, 5); and the intervals that are not chord tones (♭2, 2, 3, 4, #4 (♭5), #5 (♭6), 6, ♭7, 7).

If you’ve got a looper handy, or if you haven’t treat yourself to one from Amazon, loop an Am chord.

Try out all of the intervals over the Am chord. Some sound better than others, right? Though this will depend on your musical sensibilities.

What could you play over an Am chord?

Your first port of call will probably be the Am Pentatonic Scale. Nothing wrong with that, let’s analyze:

Am chord: 1, ♭3, 5

Am Pent: 1, ♭3, 4, 5, ♭7

What else could you play?

You could play the Dorian scale, the Natural Minor scale, the Melodic Minor scale, the Harmonic Minor scale, the Phrygian scale, to name a few.

Do you know the patterns for all those scales? No? You’re screwed.

Do you know the interval structure for all those scales? Maybe not, but you can learn it in 5 minutes!

Natural Minor: 1, 2, ♭3, 4, 5, ♭6, ♭7

Dorian: 1, 2, ♭3, 4, 5, 6, ♭7

Harmonic Minor: 1, 2, ♭3, 4, 5, ♭6, 7

Melodic Minor: 1, 2, ♭3, 4, 5, 6, 7

This might look like a lot of numbers but ALL those scales have a 1, ♭3, 5 with a 2 and a 4.

In other words, what makes them different is the remaining intervals:

Natural Minor: ♭6, ♭7

Dorian: 6, ♭7

Harmonic Minor: ♭6, 7

Melodic Minor: 6, 7

For example, if you want to evoke a Harmonic Minor sound then play the ♭6, 7 combination against the 1, ♭3, 5.

If you want a Dorian sound, play the 6, ♭7 combination against the 1, ♭3, 5.

And so on.

The 1, ♭3, 5 will always be your strongest intervals, so think of the others as adding color. Over a simple Am chord, you have a wide palette to choose from (don’t forget to be tasteful), but as we get into more complex chords, you’ll have to make more informed choices.

If you’re a little more advanced, try evoking the Phrygian scale using the ♭2, ♭6, ♭7 to color.

I recommend spending some time with this concept because it will help you make that shift from patterns to intervals, and perhaps from mindless to mindful playing. I’m sure you’ll agree that learning 5 sequences of intervals is a hell of a lot quicker than learning 5 scale patterns.

In Part 6, we look at how to analyze more complex chords.