Barre chords are almost a rite of passage after learning all the open chords. I see a lot of beginners straining their wrists and ripping their fingers to bits trying to play them; this is also the point where a lot of would-be guitar players give the instrument up due to the aforementioned incessant pain. The problem is, no one ever explains to them what barre chords are actually useful for, and more importantly, what they’re not useful for; this way you can know what you’re getting yourself into, and hopefully see that barre chords are not the be all and end all of getting somewhere on guitar.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not suggesting you skip learning barre chords altogether, but I do think you should know what they’re actually useful for so you don’t end up giving up the guitar because you can’t do an F major chord.

3 Ways to Build Up Hand Strength

1. The vast majority of beginners usually start out on acoustic guitar then move on to electric once they’ve gotten the basics down. Barre chords are way harder to do on an acoustic than on an electric… Or rather, barre chords are way harder to do on a cheap acoustic than on a cheap electric.

2. Another thing you can do is invest in a capo and put it up at the fifth fret. The capo acts as a new nut and makes barre-chording much easier due to the reduced effort needed to hold the strings down. Gradually move the capo down toward the nut, perhaps one fret a day, and you’ll find it much easier to do that F major chord.

3. If that doesn’t work, try overextending the first finger for the barre. In other words, overshoot the tip of the 1st finger so that it’s extended beyond the bass side of the neck. This creates a more secure barre.

A Man Walks into a Barre

Standard tuning is fairly versatile when it comes to open chords. You can cover a lot of ground and play a lot of easy songs with the so-called cowboy chords. Trouble is, at some point you’ll have to combine barre chords with open chords, such as the enigmatic F major barre chord at the first fret. Theoretically speaking, that F major barre chord can only show up in three different keys as major chords can only be the I, IV or V chord. This means that you’ll find F major in the following keys:

- In the key of F major it’s the I chord (quite a few songs are in F major, but you can avoid these for the time being).

- In the key of C major it’s the IV chord (tons of songs are in C major, you can’t avoid these).

- In the key of Bb major it’s the V chord (not much to see in Bb major).

The key of C major is the problem because there’s an infinite number of songs in this key that combine open chords and barre chords. You won’t find nearly a fraction of the songs you might learn as a beginner in F or Bb major as you will in C major.

Avoiding songs in C major is not the answer as the other 4 keys that guitarists play in (A, G, E, D) all involve forced barre-chording.

The Thumb-over Technique

Rather than search for songs in other keys, if you watch Jimi Hendrix, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, and many others, you’ll see them using this (frowned upon by classical guitarists) technique. Instead of using the first finger as a barre, they use the thumb to play the note on the bottom E string—in Hendrix’s case the E and A strings—freeing up their four fingers to the play the rest of the barre chord, or parts of it. I’m sure this technique evolved due to the versatility it gives you when playing rhythm, or combining rhythm and lead. The ‘proper’ barre shape only leaves you with three fingers available, and a somewhat restrictive hand position. You should be able to do this even if you have small hands because the palm of your hand ends up pressed against the back of the neck. The thumb-over also opens up a world of songs to learn from the back catalogs of Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, RHCP and many others, which you’d have a hard time playing with ‘proper’ barre chords.

When are Barre Chords Useful?

Barre chords are incredibly useful when you’re playing unaccompanied as they provide a fuller sound. They also give you access to playing chord progressions in any key, as your first finger becomes a movable nut, and you can quickly knock out a chord progression when asked.

Barre chords are absolutely essential if you want to be able to play classical pieces, which also requires added strength as you’ll often need to hold a barre chord while playing single notes before changing to another one and doing the same.

Smooth Changes

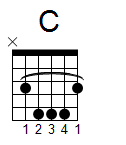

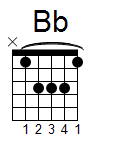

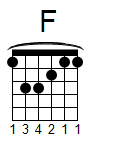

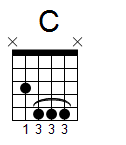

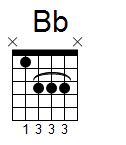

Once you’ve gotten a handle on the barre chords and can pretty much pull them off, you’ll want to get used to changing between barre chords in a progression. If you have the chords F, Bb and C (I, IV, V in F major) you ideally don’t want to be playing the F down at the nut, then race up to the sixth fret to play the Bb, then up to the eighth fret to play the C, then all the way back down to the nut to play the F again. You should instead play them as close together as possible as follows:

You can always use the fingerings below for the Bb and C chords if they’re more comfortable.

What’s Next?

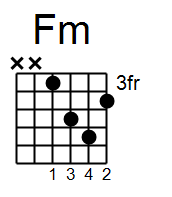

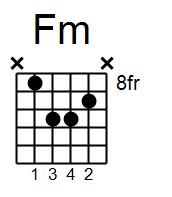

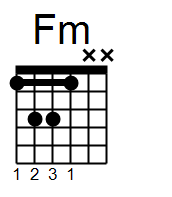

Once you’ve gotten the hang of changing barre chords in close proximity, you’ll be able to appreciate how barre-type chords move vertically across the fretboard. Check out the three F minor chords below. These are partial barre chords as they’re easier to move around the fretboard, so be sure not to play the strings with Xs.

What do you see? Most guitarists see 3 different F minor chords but what I would like you to see is the same chord just warped by the fretboard, or more precisely, the guitar’s tuning.

You may have noticed that when you tune your guitar, you compare the notes at the fifth fret until you tune the B-string. This is because the distance between the G and B strings is a major 3rd (4 frets) instead of a perfect 4th (5 frets) like the others.

The B-string is the warp zone. Any chord we use which contains notes on the B-string will invoke the warp factor and cause these notes to move up one fret. If the chord involves a note on the top E string as well, this will follow suit and move up one fret.

Compare the first and second chord shapes above. Notice that the second shape is the same as the first but as the second chord involves the B string, the warp factor is invoked, and the note moves up one fret.

Now compare the first and third chord shapes. Again, the warp factor is invoked, this time on the B and E strings, so both notes move up one fret. However, it is the same chord shape in all three cases only warped by the fretboard.

This way of moving chords was a big revelation for me and helped me to understand how they move logically on the fretboard. Happy barre-chording!