The top four strings on the guitar are a great area to exploit for tight funky chords. In this blog lesson we look at a range four-note chords and how they move in a logical, almost mathematical way, horizontally across the fretboard. I’ll keep the theory to a minimum so you can go straight to incorporating them into your playing. Let’s get funky!

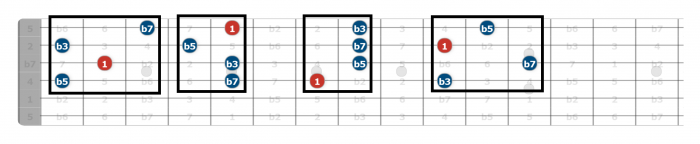

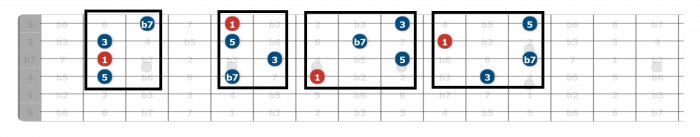

Chords, or rather chord inversions, move horizontally as shown in the fretboard diagrams below.

Look at how this four-note A7 chord moves through its inversions. You can use any of these voicings when an A7 chord is called for; remember that chord inversions are just the intervals in a chord stacked in a different order. As long as the A note is considered the root and the chord contains the intervals 1, 3, 5, b7, it doesn’t matter what order they’re played in, they’ll still be an A7 chord. What’s more important here is the sound, one chord (inversion) may be more to your liking, or better suit the playing situation, than another. You can also throw them in when comping on A7 instead of chugging on an A7 barre chord.

You’ll notice that as the chord shape moves horizontally across the fretboard, the interval stack changes; they now follow the numerical order of the intervals horizontally to form the next chord.

A four-note chord will have four inversions (four stacking options), a five-note chord will spawn five options and so forth. This information is well-worth knowing as it will take the mystery out of chord inversions.

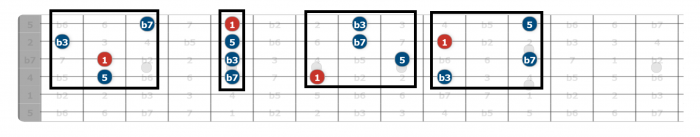

Let’s apply this to Minor 7 chords.

Again, these four inversions of Am7 are formed by moving their intervals in a horizontal fashion, just as we did with the A7 chord.

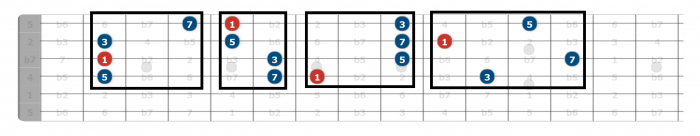

Let’s take a look at their Major 7 counterparts:

Major 7 chords follow the same idea as they move logically up the fretboard. Remember to transpose these chords to other root notes as they are all movable.

Our final set of chords is from the m7b5 family: