It’s no secret that the guitar lends itself well to creating visual information such as chord shapes, scale boxes and arpeggio patterns, and even riffs. In fact, pretty much anything on the guitar can be reduced to a shape, box or pattern which creates a ‘learning’ system akin to painting by numbers, sidesteps music theory, and as long as you build up a certain amount of technique, you can play extremely complex guitar parts without actually knowing how or even why they work. This is also why you shouldn’t get depressed about all those 9-years-old ‘virtuosos’ on YouTube reproducing the works of Steve Vai et al. What might depress/elate you though, is the following realization regarding boxes, shapes and patterns.

It’s All Backwards

If you think about it, the shape, box or pattern should be the byproduct or result of learning, not the object of it.

Let me explain.

When you go to learn a chord, let’s say a B7#9; I imagine you can easily pull the ‘Hendrix’ shape out and fire off a B7#9 chord at will. This is all well and good but by going straight to the shape, you skip the entire learning process.

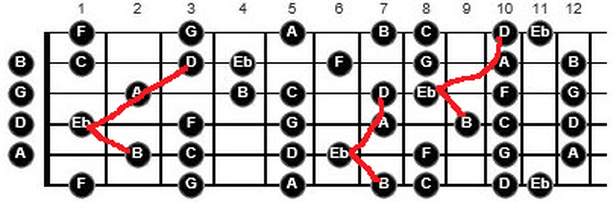

The learning process could be as follows: An B7#9 chord contains the intervals 1, 3, 5, b7, #9 and the notes B, D#, F#, A, D (simplified spelling). Through study you learn that the 5th (F# in this case) is often left out of the chord because a) if you need to reduce the number of notes in a chord for practical purposes, the fifth is the first to go, or b) it sounds better without the fifth. You’ll also learn that B7#9 is diatonic to the C Melodic Minor Scale (as you can see below), which means you know which chords work with it and that you can play the seventh mode of the melodic minor (the altered scale) over it.

Using your knowledge of the notes and/or intervals in the chord, you could then come up with the above shapes on the fretboard and you have your shape as the result of learning; it’s the takeaway that helps you remember what you learned. If you followed this process, when you recall the shape, you recall the learning too.

If you didn’t follow this process and just learned the shape and labeled it B7#9, you have no idea what chords it works with, what the diatonic scale is, what notes are in the chord, what intervals are in the chord, why there’s no fifth, what scales you can play over it (other than the minor pentatonic); in other words, you know a chord shape on the guitar called B7#9, which you use in Purple Haze or Foxey Lady, but little else.

Arpeggios

The same is true of arpeggio and scale patterns, and this is the difference between you and John Petrucci – you may have learned how to technically reproduce some ridiculous F#m7b5 sweep arpeggio with tapping, but he’s the one that knows what notes and intervals are in it, as well as how and why it works. For him it’s a functional piece of musical knowledge, while for you it’s a party piece.

Again, we see that the pattern should be the result of knowledge, not the knowledge itself. I’m not saying you shouldn’t learn patterns; all I’m saying is that you should know how and why those patterns work, especially if you want to progress from party tricks to using this stuff productively in your own playing.

Scales

As you may realize, running up and down a scale pattern (no matter how fast) will never create a memorable guitar solo. Not all notes in a scale are created equally, so treating them equally will make your solos sound very bland indeed. If you know where and what the important intervals are in a scale, you can create far more interesting lines, as we saw in the How to Create Melodic Guitar Solos tutorial.

Creator of Ruts

It won’t surprise you then to learn that endlessly memorizing patterns is one of the main causes of getting into a rut on guitar. Most guitarists come to the conclusion that to get out of this particular rut, they need to learn more patterns, or different patterns… Hopefully now you can see that while this might get you out of a rut temporarily, in the long-run you’ll get stuck there again and again.