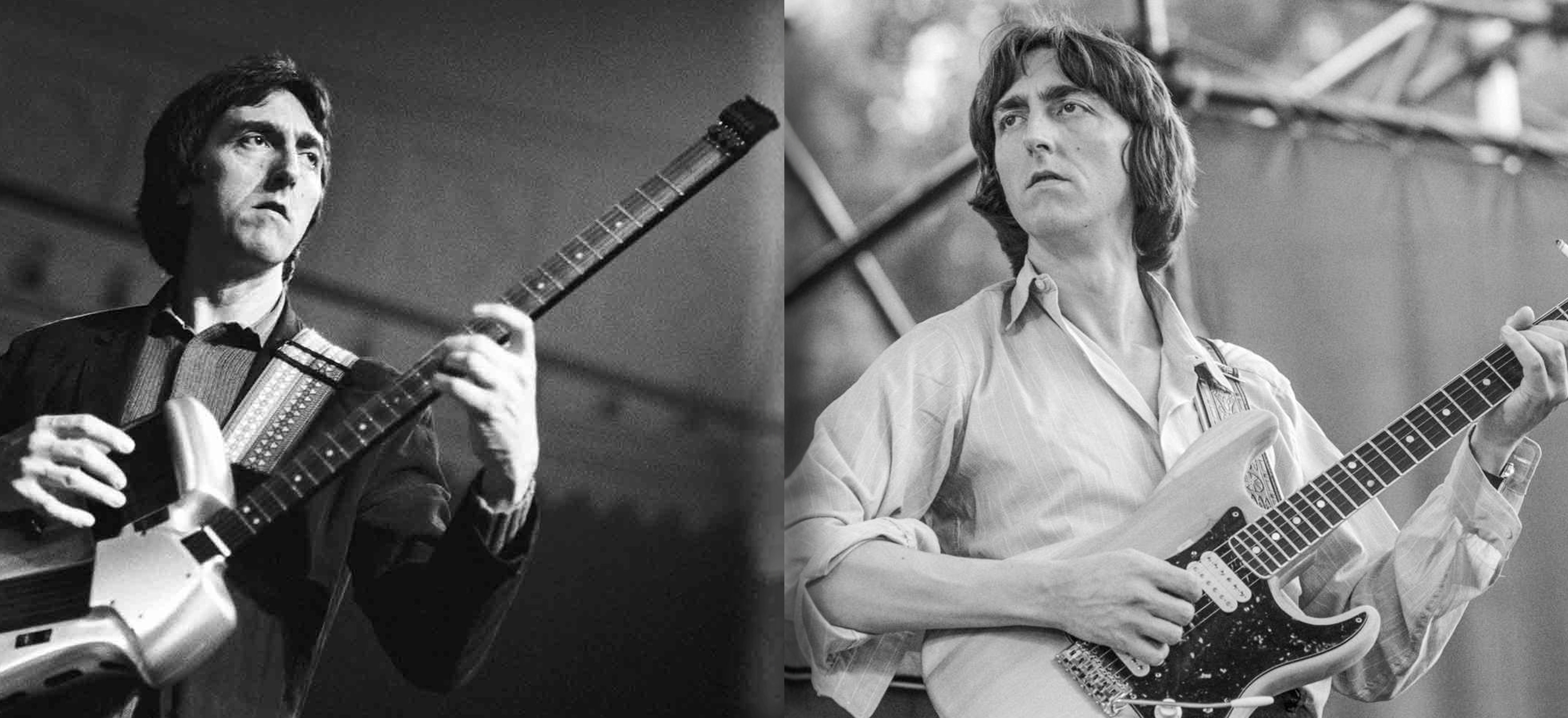

I have a lot to thank my first guitar teacher for; in particular, the day he introduced me to the music of Allan Holdsworth. Around the same time, he’d also turned me on to Jeff Beck and John Scofield—both of whom shape and influence my playing to this day—but there was something about Holdsworth’s music that connected with me on a deeper level. It was both creatively outrageous, liltingly beautiful, and deeply intriguing. The next time I found myself in a music store, I picked up a copy of, ‘The Sixteen Men of Tain’, which had just come out, and coincidentally was Allan’s first album release in a number of years. To this day, it’s still my favorite Allan Holdsworth album and a constant inspiration. My intrigue was then heightened when I discovered Allan’s REH video, and so began the quest to understand how Allan perceived music and absorb his approach to chords, scales and improvisation.

I think anyone who undertakes a serious study of any instrument needs a mentor, whether in person or someone who creates a healthy obsession in you to push yourself and your own limits; and this is what Allan represented for me, though regretfully I never got to meet him or see him play live.

As you may know, Allan pretty much discarded traditional music theory in favor of his own system for creating music, unusual chord voicings, and searing improvisations. In the REH video, he goes into it somewhat and after a few watches I was able to grasp the basic idea, which actually has a childlike simplicity to it; and this is where a lot of players trying to understand his approach completely miss the point. Like Allan, I am also heavily drawn to improvisation, so it was obvious to me that he had created a system for improvising over chord changes which, after considerable study, would allow him to improvise as freely as possible all over the guitar neck without the constraints of a more traditional approach.

I read that Allan created several tomes of neck diagrams and scale patterns which he dubbed, ‘the phonebooks from hell’, and which became his study material. I can imagine what’s in those tomes as after understanding where he was coming from, I began to compile my own collection of fretboard diagrams, though nowhere near as exhaustive as Allan’s. In retracing his steps, you get a glimpse of the genius mind at work that came up with a simple concept and took it as far as humanly possible, the driving force of which was creativity and improvisation, with those unusual chord voicings almost a byproduct. In a way, it’s the perfect marriage of the structure and layout of the guitar to creative expression stemming from a holistic approach to music. It breaks all the rules, unapologetically, and replaces them with tangible concepts for the creative right brain to devour. It was these concepts that allowed me to advance in leaps and bounds with my own improvisation, and finally unleash the creativity that had been held back by my lack of understanding of traditional music theory—and believe me, I tried to understand it!

If you think about it, there are very few guitar players that truly improvise when they go to take a solo. John Scofield calls it, ‘sped-up composition’, which is a pretty much what you should be doing if you’re truly improvising. Allan didn’t have any pre-fabricated licks or runs, and certainly didn’t script or rehearse what he was going to improvise on any given night. When you see him improvising, it’s from the heart; he’s not stringing a bunch of licks together like most other players.

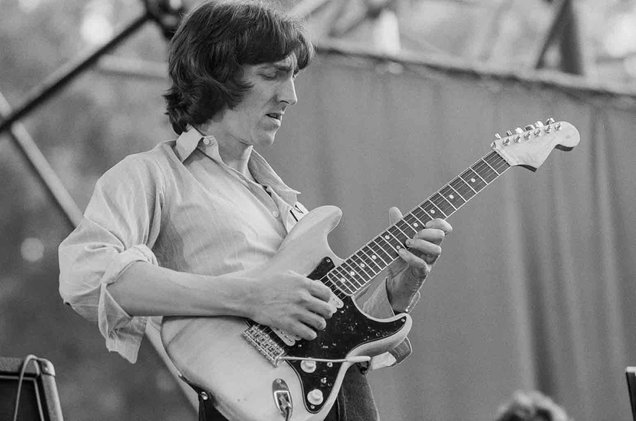

Allan’s hands were an extraordinary ergonomic fit for the guitar, but more so than this—he used them to their full potential. Take a closer look at the way Allan’s left hand moves around the fretboard, it’s strictly one finger per fretted note, no matter the stretch; something that few other players consider. His use of the legato technique was driven by his dislike for the noise of the pick hitting the string, and his preference for a soundless attack akin to that of a horn player.

Jimmy Page is quoted as saying, ‘I believe every guitar player inherently has something unique about their playing. They just have to identify what makes them different and develop it.’ I believe Allan, in being relentlessly true to himself, took his love of improvisation and ran with it to become one of the most unique guitarists that ever lived, and in turn one of the instrument’s greatest innovators.

RIP Allan, you will be sorely missed.